The Great Diamond Hoax

In 1871, amidst the fervour of post-Gold Rush San Francisco, a city teeming with tales of fortune and the echoes of prospectors' dreams, two frontiersmen wandered into the main branch of the Bank of California. Philip Arnold and John Slack, their faces weathered by the frontier sun and with a thick layer of dust on their clothes, cut striking figures amidst the polished marble and gleaming brass of the bank's caged counters.

At the cashier’s desk, Arnold flashed his tobacco-stained grin and said they needed a safety deposit box for some “property of great value.” With some skepticism, the two were shown into the bank’s vault and there produced a pouch of stones and gems – mostly beautifully rough diamonds. Slack remained silent as Arnold explained they had found a section of the plains in the American west covered with diamonds and other stones, and they had simply scooped them up and now needed somewhere to keep them safe. The man from the Bank of California gave the pair a receipt and the stones were locked away, with Arnold and Slack disappearing back into the busy San Francisco streets.

The Initial Pitch

Arnold and Slack, Kentucky natives, each bore an adventurous and somewhat notorious past. Philip Arnold, a former miner and bookkeeper, and John Slack, a former soldier turned gold prospector, were well-equipped for a scheme of grand proportions. Before the end of the day, the branch’s manager had got in touch with the founder of the Bank of California, a man called William Ralston. At the time, the gold rush mentality had hooked America and now the promise of the West had come to life. Here was a tale of untold riches made manifest in the heart of the city. Ralston had invested in anything that made money, from the railway to hotels to mining and the pouch of gems sitting in his bank’s vault sounded like the perfect opportunity.

Arnold and Slack found themselves summoned to Ralston's plush office. There, the banker subjected them to a thorough interrogation. At first it appeared the two prospectors were frightened and didn’t really want to talk, but eventually with Arnold once again as the spokesman, they began to discuss their find. Arnold said the field was in “Indian country” and was littered with everything from diamonds to rubies, so prevalent even someone digging with their hands would come home a millionaire.

One thing Arnold was clear on was that the pair would not reveal the field’s location, even within the nearest thousand miles. Word quickly spread California and before long groups of diamond hunters were, to no avail, digging across all of the southwest for this apparent field of gems.

In the meantime, a valuer was brought in and said that the stones deposited in the bank were worth around $125,000 ($3 million today1). Realising he was onto something potentially massive, Ralston needed help and for that he turned to an old friend, Asbury Harpenden.

Assembling the Investors

Asbury Harpenden was a bizarre character with a tumultuous past. As a teenager he had run away from home to join an ill-fated invasion of Nicaragua in 1856 led by a mercenary group dedicated to turning the South American state into a privately owned pro-slavery colony of the United States. Harpenden eventually returned home and his father, keen for his son not to invade anywhere else, sent him off to California. Before long, Harpenden had become wealthy from mining but by 22 had decided he would go back to his old ways.

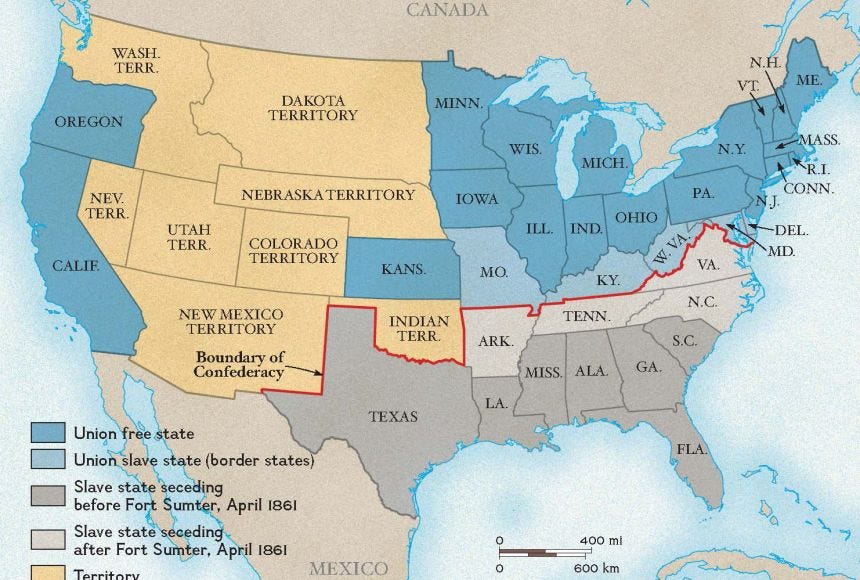

In 1861 the American Civil War between the United States and the Confederate States had begun over the issue of slavery. Harpenden saw an opportunity and joined a group planning to seize San Francisco from the United States and turn it into a breakaway country which would be called the Pacific Republic, where slavery would be legalised and span the western coast from California to the border with Canada.

The Pacific Republic plan was disrupted at the last minute and Harpenden fled, with the assistance of a secret society known as the Knights of the Golden Circle, to the east coast where he found his way to Richmond in Virginia, the capital of the Confederate States of America. There he obtained a letter of marque, a document that allowed him to become a privateer at sea for the Confederacy. With this letter he planned to return to San Francisco and take a ship into the Pacific and wreak havoc on American shipping, sending loot back to the Confederacy and help them win the war. On the very first night aboard his ship, Harpenden was boarded and captured by the US Navy and quickly sentenced to 10 years in Alcatraz for treason.

Luckily for Harpenden he only had to serve a few months in prison before Abraham Lincoln’s amnesty for Confederate traitors was put into force and the failed pirate gained his freedom. He returned to mining and grew his fortune, eventually moving to London in 1871 to set up a financial newspaper called the London Financial Review. While with the pretence of a newspaper, really it was dedicated to getting investment from British banks and financiers in American mining schemes, many of which lacked any credibility. It was at the newspaper’s offices that Ralston wrote to him. In his (unreliable) memoirs2, Harpenden states that the urgent telegram Ralston sent cost $1,100 ($30,000 today) and that it begged him to come to California:

He said that diamonds of incalculable value could be gathered in limitless quantities at nominal expense; that they could be picked up on the ant hills; that at a low estimate it was a $50,000,000 proposition; that he and George D. Roberts, a well-known mining man, were in practical control. Finally he almost demanded that I should drop everything, take the next steamer and act as general manager.

The extravagance of his language alone seemed to me to indicate that he was laboring under some strange delusion. However, diamonds or no diamonds, I was in no position to stir. I cabled him briefly that my business in London was of too vital importance to admit of considering other engagements.

George Roberts was another San Francisco businessman who had been approached by Arnold and Slack, Arnold had told Roberts that the discovery must remain a secret but all that did was ensure it spread farther and wider.

However, despite his initial reluctance, Harpenden could not ignore the lure of a potential fortune. He wrote that despite his refusal to help, expensive telegram after expensive telegram began to arrive. If you consider $50 million from 1872, today it would be be worth billions in terms of economic value, and the only people who knew how to find it were Arnold and the silent Slack. The word spread in London and America, with many calling on Harpenden to find out more. In his memoirs, Harpenden claims that even the world-famous financier Lionel de Rothschild asked to see him:

Baron Rothschild sought an interview. He asked me what I knew about the diamond fields, and I frankly showed him Mr. Ralston's cables. He read them with interest and asked me what I thought myself. I told him that while I had great confidence in Mr. Ralston, I thought he must have been imposed upon in some way, and that in due season the bubble would burst.

Baron Rothschild mused a moment. "Do not be so sure of that," he said. "America is a very large country. It has furnished the world with many surprises already. Perhaps it may have others in store. At any rate, if you find cause to change your opinion, kindly let me know."

This remark, made by perhaps the keenest financier in the world, was enough to set any one thinking hard.

Before long, Harpenden had given in and was on his way to San Francisco, arriving in May 1872. Their Arnold and Slack met with Ralston, Harpenden and Roberts. The three offered to buy out Arnold and Slack, but as they refused to share any details of the location nor let anyone go with them, the deal would be contingent on Arnold and Slack bringing more diamonds from the same location as a feature of good faith, to which the pair agreed.

Within just a few months, Harpenden met Arnold and Slack at a railway station in the small Californian town of Lathrop. Slack was asleep while Arnold guarded a large buckskin package, when Slack woke the two told Harpenden that they had found a huge quantity of stones that they reckoned to be worth $2 million ($51 million today). So many, in fact, that the diamonds had to be put into two separate sacks, with one unfortunately lost in some river rapids despite their best efforts. Despite this, Arnold hoped, Harpenden and his business partners would be happy with the sack full of just $1 million worth of diamonds in it. Harpenden thanked the pair and said he would be in touch, when he got home he cut open the sack and poured it over his billiard table, which was quickly flooded with sparkling diamonds and rubies.

The very next day Harpenden and his fellow investors gathered together, along with a few other mining investors. The group agreed they needed to act fast and came up with a plan. A sample of the diamonds would be sent to New York, to be examined by Charles Tiffany, the founder of Tiffany & Co. The group also sketched out the corporation they would establish, and what laws would need to be changed to guarantee the rights over the location. They also told Arnold and Slack that the time for secrecy was over, and that they would have to agree to a visit to the diamond field with the investors and a diamond expert, to which the pair reluctantly agreed in return for $50,000 each (over $1 million today) – paid upon a satisfactory report from Mr Tiffany and the site visit.

The Appraisal

The excitement was palpable as Harpenden took the sample gems in a bag to New York, to a house in the city where Mr Tiffany and other notables like congressmen and bankers were eagerly waiting. Harpenden opened the bag and offered to the world’s greatest authority on precious stones. Tiffany quietly began to remove the gems, a few diamonds, then some rubies, emeralds, even sapphires. He sorted them into little piles on a table, holding some up to the light with his expert eye. "Gentlemen," Tiffany said, “these are beyond question precious stones of enormous value … I will report to you further in two days."

Two days later, Tiffany wrote to Harpenden with the official report of his gemologists. The small selection of stones from the Arnold’s second expedition were, Tiffany wrote, worth $150,000 ($4 million today), meaning that the sack Arnold handed over at the railway station would be worth well over $1 million. The report spread like wildfire and every investor in America wanted a piece of the pie. The next stage was a site visit for the investors with Arnold, Slack, and the mining expert - Henry Janin.

The Site Visit

At Omaha, in Nebraska, Harpenden and his New York investors met Ralston and Roberts coming from San Francisco by rail. Before the two groups could carry on, Arnold began to cause problems, furious that he and Slack would have to reveal the location of this wealth to all and sundry. While the investors were cynical, they relented and the San Francisco bankers were sent home. Harpenden, Janin, Arnold and Slack, got off at the end of the railway in Rawlins, a settlement in southern Wyoming. There they set out with an expeditionary group, led by Arnold and Slack. Harpenden writes the journey was erratic, walking up and down hills for four days in search of landmarks. Eventually Arnold declared they had arrived. Harpenden was sure he heard a train whistle, impossible given how long they had been walking and Arnold smiled and said it couldn’t be as they were more than 100 miles from the nearest railway.

The group secured their horses and Arnold and Slack shrugged and said they could look wherever they wanted; the whole place was filled with diamonds. With a few shovels, everyone split up to try and be the first to find a gemstone. Within just a few minutes, one of Harpenden’s friends yelled, holding up a large diamond. For the next few hours, such finds of diamonds, rubies and emeralds were unending. For two days the group camped and worked the field and by the end of it Janin had decided it was the real deal and endorsed Arnold and Slack’s finds. This field, Janin said, would control the entire world’s gem market. Janin would later write in his report that with just 20 workers, the field would generate $1 million ($26 million today) of diamonds each month. The investors returned home while Arnold and Slack went their own way, waiting their payment.

By late summer 1872 and with Tiffany and Janin’s reports in hand, it was not long before the “San Francisco and New York Mining Company” had been formed with share capital of $10 million ($4 billion today when considered as wealth), $2 million of which was offered out and immediately snapped up by some of New York and San Francisco’s wealthiest as well as Baron Rothschild. Ralston and Harpenden set up offices across the country, and newspapers around the world were filled with excitement.

The investors were left with the matter of Arnold and Slack, in addition to their original payment of $100,000, the pair were convinced to sell out their remaining interest for a further $300,000 which was cashed immediately by Arnold. Having given Harpenden the true location of the fields, Arnold and Slack said they would return to Kentucky. It was at this point Harpenden realised that the four day zig-zag journey from Rawlins had only taken them 25 miles, not the 100 Arnold had claimed.

The Unravelling

It was to the field, 25 miles from Rawlins, that the US Government sent a man called Clarence King in November 1872. King, a geologist, had been despatched to examine the small corner of America that could become one of the most valuable places in the world. One of King’s colleagues had been shown the diamonds Janin found, which seemed unusual for the area. King could not get the exact spot out of Ralston and Harpenden but was able to engage the same guides they had, who took the geologist to where the expedition had been. There, King and his group began finding gems just as Harpenden had a few months before. It was agreed after several days that the discovery was genuine and the group would go to San Francisco and talk with the company’s executives. Just before they left, a German member of King’s group who had been pocketing a good number of the diamonds found held one up to the light and yelled for King.

“Look here, Mr. King," the German said. “This is the bulliest diamond field as never was. It not only produces diamonds, but cuts them moreover also.”

In his hand he held a great diamond, found in a hole in the ground but half of which had been obviously tooled and polished by a diamond cutter. King grabbed the diamond out of the German’s hand and realised that everyone from Ralston, to Baron Rothschild, to Charles Tiffany, had all been duped. The group began looking harder and realised that the “anthills” that many of these stones had been found in were carefully constructed set pieces where exactly eight inches down a single uncut diamond sat. Similarly rubies and emeralds had even been jammed into the crevices of boulders and all designed to be found. During this, a smartly-dressed city man approached King’s party and asked if they had found any diamonds. He turned out to be J.F. Berry, an investor in Ralston’s mining company that had followed King and watched him with a telescope to try and see the diamond field for himself. Being told of the fraud, Berry, a wealthy New York diamond dealer, told King how glad he was to have the chance to sell the stock short and quickly left the scene.

Realising the impact his discovery would have on the market, King dismissed the idea of a meeting with Ralston’s group and rushed to the railway station where he immediately sent a telegram to the company, the field had been “salted” - a term to refer to the planting of precious metals in an otherwise empty place. It had taken off as a trend in the gold rush to sell empty mines to speculators, and had even brought down a governor of a western state who had salted diamonds to try and bring in investors. Dozens of America’s richest and most powerful men had all fallen for Arnold and Slack’s ruse and the shares of the San Francisco and New York Mining Company weren’t worth the paper they were printed on. But how had they done it? The embarrassed investors hired an agency of private detectives and soon the story began to emerge.

The Salting

In 1870, Philip Arnold and John Slack had made a bit of money opening and selling mines in the American west. By that year, the pair had $50,000 in ready cash and with that money Arnold took a boat to Europe. He never travelled through American ports, departing and returning instead from Canada. In late 1870, Arnold appeared in the diamond markets of Amsterdam. Sellers there were shown Arnold’s photograph by the detectives, they remembered him. He was a flashy American who had come and bought cheap and inferior rough diamonds in large quantities as well as a few other gems. With these, he returned to America and with Slack went to the Bank of California in San Francisco.

When Ralston and the others took the bait, the pair realised they needed more stones as the investors would expect to see an actual diamond field. While Slack remained in America and Harpenden was in New York, Arnold returned once again to Europe via Canada, but this time sailing to London. In London, the detectives learnt, he toured all of the largest gem dealers buying up huge quantities of rough stones. He insisted he was only interested in extremely low quality diamonds and gems, the type used for drilling. The largest dealer showed him a pile, expecting Arnold to select a few but the American turned and asked “How much for the lot?”

Arnold handed over $15,000 in cash - a sum equivalent to $400,000 today. Pocketing the packaged diamonds, he set off for America. Arnold met Slack in Rawlins and from there they selected that little field 25 miles from the station. Content with the spot, they used metal rods to make long holes in the ground where they would then drop a diamond or two before using their feet to refill it, making the ground seem untouched. From there the pair met Harpenden in Omaha. As we know, Arnold and Slack disappeared once the investors had the satisfactory reports in hand and weren’t present when the entire scam came crashing down. With expenses and other payments included, the pair had made a profit of more than $600,000 ($15 million today when considered as wealth).

The Hunt

Harpenden and the detectives tracked Arnold to Hardin County, Kentucky. There, they found him living on a sprawling 500-acre estate, complete with a massive house and a custom-built, impregnable safe. It was in this safe that Arnold had stashed his ill-gotten gains. Once the salting had been uncovered, several of the investors sued Arnold but he denied he had ever salted the field, submitting as evidence the reports of Tiffany and Janin. Arnold fought the legal battle for a time. Eventually, though, he settled with one of the investors: $150,000 in cash, drawn from his great safe, in exchange for immunity from further suits. Arnold would later open a bank in Kentucky, eventually getting into a dispute that had him shot and left him with a wound that left him vulnerable to illness and he died from pneumonia in 1878. Slack, meanwhile, had totally vanished and likely only taken a small portion of the takings before moving to New Mexico to become an undertaker, where he died peacefully in 1896.

The other members of this bizarre cast had no stranger endings to their stories. William Ralston, the first to fall for the ruse, would be found dead in the Pacific Ocean just three years after the Diamond Hoax. He had put all of his money into the Palace Hotel in San Francisco, leaving him vulnerable after the crash of stock in his bank in a market panic. Meanwhile Clarence King, his expedition complete, went on to a distinguished career. He would later serve as the first Director of the US Geological Survey and curiously also by night pretend to be an African-American railroad worker3. Harpenden went to New York where he continued to drive market speculation. Embarrassment drove many of the other investors into a quiet retirement from public life.

As the dust settled on the Great Diamond Hoax, the nation was left to marvel at the sheer audacity of Arnold and Slack's scheme. In an age of rapid industrialization and boundless opportunity, the notion of vast, untapped wealth lying just beyond the horizon had captivated the American imagination. The diamond fields of Wyoming, though ultimately a mirage, were but a glittering embodiment of this dream.

For a brief, shining moment, Arnold and Slack had stood at the pinnacle of society, feted by millionaires and celebrated in newspapers across the land. Their ruse had exposed the gullibility and greed of some of America's most prominent figures, men who prided themselves on their business acumen and judgment. In the end, the prospectors had walked away with a fortune, leaving behind a trail of shattered egos and emptied wallets. The Great Diamond Hoax would go down in history as a masterclass in deception, a grand illusion conjured up by two unlikely sorcerers of the American West.

Today, the site of the diamond fields, once the epicenter of one of the greatest swindles in American history, sits quiet and largely forgotten in the Wyoming wilderness – with the only hint of it being named Diamond Peak. But the legacy of the hoax lives on - in the enduring fascination with tales of cons and schemes, in the hard-learned lessons about the perils of easy money, and in the uniquely American dream of boundless wealth waiting just over the horizon.

What I’ve been reading:

The Order of the Day by Eric Vuillard - This is a very short book, translated from the original French, set in the context of the Austrian Anschluss. Really it’s an essay but with the tempo and the readability of a really good novel.

The Battle for the American West by Oliver Roeder - It was this recent FT piece that actually inspired this week’s post. It tells the story of the checkerboard of public and private land that spans Wyoming and how ladders are causing federal court disputes.

A History of the World in 47 Borders by Jonn Elledge - Jonn is a friend and we share an interest in the absurd social and political geography of the modern world. If you have this sickness too then I highly recommend his latest book.

I use Measuring Worth for making calculations of the value of historic dollar amounts today. They use calculations that aren’t simply based on inflation but look at the labour and economic value in context.

The followi9ng statement is a lie. "In 1861 the American Civil War between the United States and the Confederate States had begun over the issue of slavery." Some of the states involved never mentioned the issue, and this misconception has been flung far and wide.

My 3rd Great Grandfather, J.P. Sanderson, wrote Florida's secession document. Florida is one of a handful of states that did not list that issue in stating the reasons for secession. What followed is akin to what Russia is doing to Ukraine in 2024.

You are not free if you cannot leave. Slavery started legally in Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut. Like a cancer it spread through the United States. Many people bought stock in slave ships and made a handsome profit, and some of those profits, to this day, that were invested for Harvard, Yale and other ivy league universities continue to provide a revenue stream for them. People have been trained to blame the South for the issue, but let's not forget where it started, and learn that in the South only 1 out of 10 soldiers had slaves. The first slave owner in our country was a black man!

Fascinating. Did Rothschild end up falling for it as well, do you know? Or was he on the wrong side of the Atlantic to have gotten in on it?