In Caracas Cathedral is the grave of a man who was born nearly 250 years ago and almost 5,000 miles away from South America. Gregor MacGregor had been buried in 1845 with full military honours and the president of a young and independent Venezuela presided over the funeral.

Tributes were paid to the man who had helped fight Napoleon before going to South America to help lead Venezuela’s war of independence in the 1810s.

What’s doubtful, however, is that the funeral’s eulogy mentioned Gregor MacGregor’s other claim to fame. In 1825, his over-active imagination and desire for money single handedly caused a run on the Bank of England and the closure of dozens of other banks across Britain.

It all began in 1820 when MacGregor, on his way back from Venezuela, stopped off in Honduras to speak to the local king. Following an exchange of rum and jewels, MacGregor was given 8,000,000 acres of prime Honduran swampland.

Safely back in Britain, MacGregor had used his journey to conjure his newly found land into the form of a country he called Poyais and made himself its king. Despite there being no real settlements there, he told all of London society that his palace sat in a capital of 20,000 citizens and that his farmers had three bountiful harvests each year. To accompany a constitution and book of laws was even a 355-page guidebook to Poyais that included advice to travellers and sketches of this fantasy.

An excitable British public fell for it all hook, line, and sinker, and rich off the Napoleonic wars they saw an opportunity to get even richer. With promised interest rates of 6 per cent, MacGregor quickly closed a £200,000 bond issue in 1822. Hundreds of others bought up land in Poyais, which went for four shillings an acre.

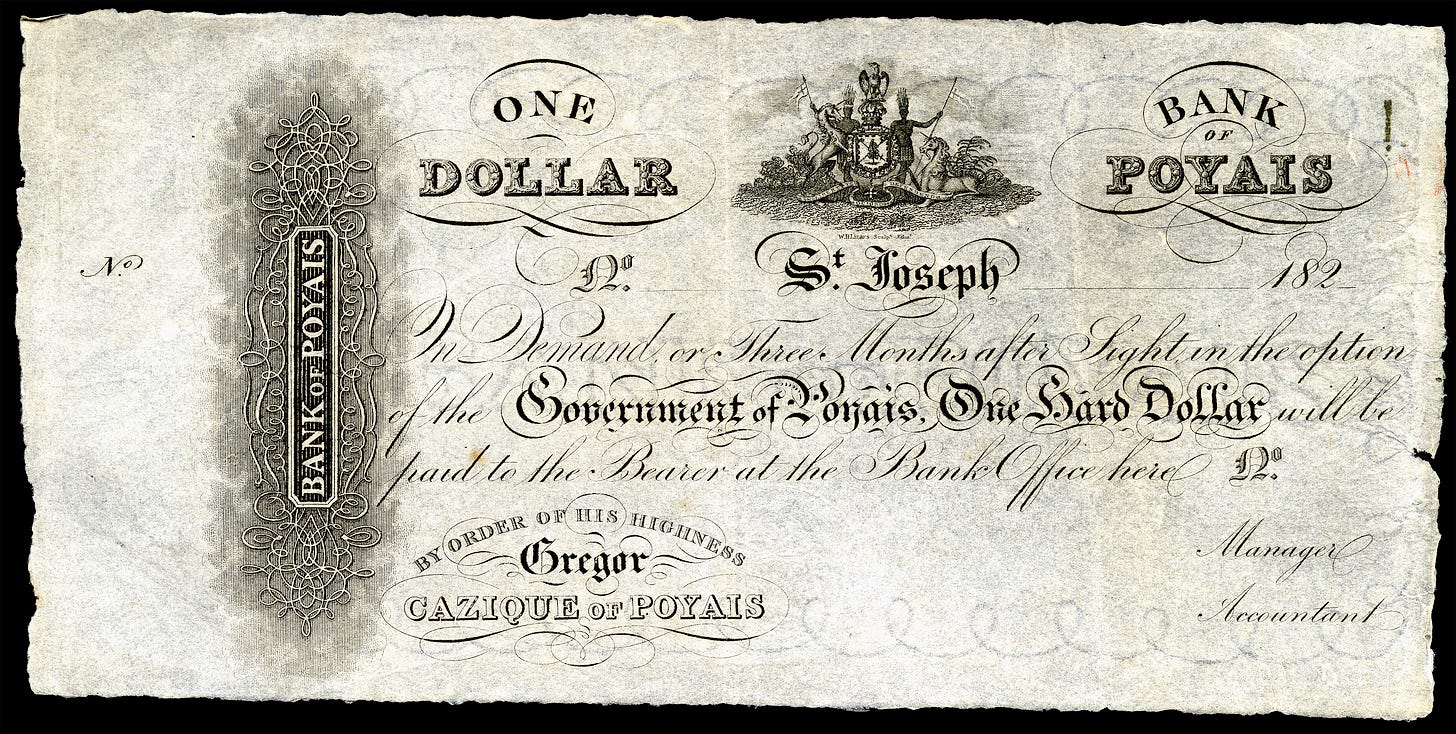

Not only was there fictional land on offer, but MacGregor and his friends had generated an entirely fictitious society. Poyais had a tricameral parliament, its own titles of nobility, and a remarkably secure banking and financial system. It all went so far that an ambassador of Poyais, who did not even know it was a fantasy, presented letters of credence to King George IV.

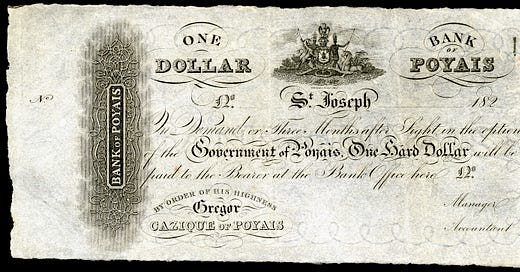

The problem with selling thousands of acres of a country’s prime colonial land and selling commissions in its army, is eventually they will want to see it. In 1823, four ships filled with settlers, soldiers, and civil servants due to run the administration of Poyais set off for its supposed capital: St Joseph. Most were fellow Scotsmen of MacGregor and were excited to be heading to land where there were said to be “globules of gold” scattered on the ground. As the settlers lined up at the docks to say goodbye to their king, MacGregor had them hand over any British currency for which he gave them completely worthless Poyais dollars.

When the first ship docked, the inhabitants did not find the promised opera house or royal palace but instead a local tribe and two American hermits who had come to this empty land for solitude. The colonists on the first two ships were eventually rescued and the remaining two diverted on hearing the disappointing news, while the Royal Navy intercepted a further five ships filled with settlers

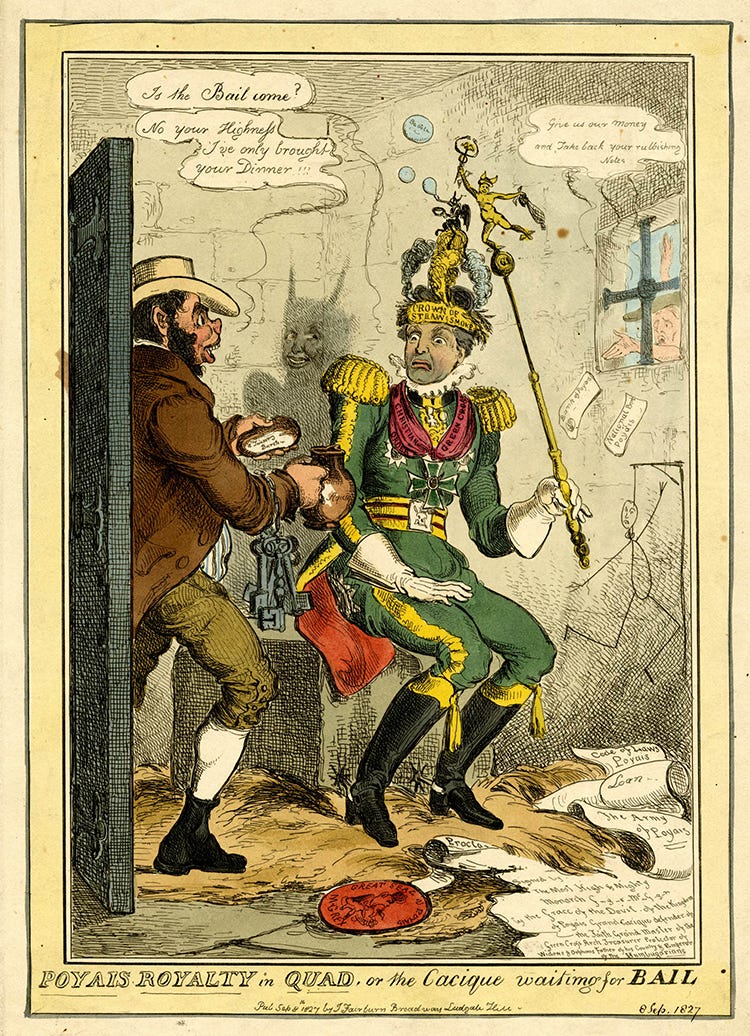

By 1824, a few dozen of the surviving colonists began to trickle back to Britain and the truth emerged. Conveniently, MacGregor had already fled to France where he was conducting the same scheme there but with suspicions rising the French would-be settlers of Poyais were not allowed to leave and MacGregor disappeared once more.

He would later be arrested in France and, after a trial, be acquitted due to claiming that he himself had been the victim of a fraud and embezzlement and that the settlers had gone to the wrong place. He returned to England and was once more arrested and released after making similar claims. The public did not forgive him and he became a figure of ridicule. Even the local king in Honduras revoked his original land grant.

As the truth emerged and it became clear the Poyais bonds would never be redeemed, the London market went into chaos, now known as the Panic of 1825. 12 major banks in Britain closed and in total 70 collapsed thanks to MacGregor’s fantasy and a general over eagerness for South American government bonds.

The country banks that had helped finance the Industrial Revolution went under. Many successful middle class Britons had invested their life savings in land they had never seen and the effects were disastrous, with bankruptcies doubling that year alone.

With no hope in Europe, MacGregor fled to Venezuela where his misdeeds in England were unknown and he was given a pension for his revolutionary service and where he died peacefully in 1845.

To this day the Poyais affair serves as a stark reminder of the enduring human susceptibility to grand promises of easy wealth. While financial regulations have significantly evolved since MacGregor's time, modern investors still face the appeal of an old-fashioned bubble.

Readers may be interested to know that in 2024, what would have been the land of Poyais in Honduras remains undeveloped.

I stumbled on this today. Terra Nullius is a History Nerd's dream. Looking forward to reading more!

Thanks for doing Poyais! It's a fascinating cautionary tale. I believe some of MacGregor's victims actually *defended him* after they made it back, because the cognitive dissonance wouldn't let them believe how they'd been straightforwardly taken in. They needed to believe it was real, that's a familiar psychology of fraud victims. From Scotland's point of view, to have one disastrous attempt to colonise Central America could be misfortune - but to have two (Darien and Poyais) looks like carelessness...