Policing at the Speed of London

Before the lights, there is always a voice. “From Met Control, units on the I-India Grade now…” and the borough inhales as one.

The Metropolitan Police grades calls for service in three ways. I‑grade (Immediate, 15 mins), S‑grade (Significant, 1 hour), E‑grade (Extended, 24 hours). Each grade has its own risk but also a reputation amongst officers.

This is different to my usual writing but I hope it will be of interest to my readers. From 2020–2025 I had the chance to serve on a busy Met emergency response team in central London; this is how a shift felt, with all of our jargon and slang in bold on first mention.

This post is a tribute to the amazing work that the men and women of the Metropolitan Police do every single day and I hope they enjoy reading it.

06:58 - Briefing

A response shift in central London starts in a room that smells faintly of unwashed body armour and freshly cracked cans of Monster. A picture of the King is stuck to the wall with evidence tape. It’s 6:58 a.m. and Early Turn is about to begin. A young in service officer scrolls the briefing slides on a big screen: names and faces who’ve “come to notice”, addresses to keep in mind and in our pocket notebooks.

One of the Sergeants — a skipper — reads out the assignments while our Inspector — the Guv’nor — sits beside her. The Met patrols in pairs, and supervisors must navigate the politics (and the odd retired romance) that make some pairings impossible. I’m paired with a good friend and we give each other a nod across the room.

Briefings are theatre in miniature: a wry aside for the officer who as always slides in at the last minute, clip-on tie in hand; a rippling laugh at an ugly mugshot on the briefing; and a quiet word to the probationer too new to have been issued his name tag.

We file out, grabbing a few pairs of latex gloves from the box by the door. Best to double-glove; you don’t want to touch half the things we’re about to touch. Then it’s vests on and a hunt for car keys.

The Met dresses as it always has: stiff white shirt, black tie, dark trousers. Then the reality of this century gets bolted on top: stab vest, radio, a body-worn video camera with a little red blinking light. Our belts hold an extending baton, metal cuffs, tourniquet, and a small can of pepper spray. Unlike most countries, almost all British frontline officers do not carry firearms. Some will clip on a Taser; it isn’t mandatory.

Keys live in a filing cabinet near the skippers, and the post-briefing stampede has a pecking order. The nicest cars — the Area Cars — are reserved for advanced drivers with years in and the training to match. Next rung: IRVs (Incident Response Vehicles), for those trained to run blue lights to calls. The dregs are the Pandas — A-to-B only, no lights or sirens for their drivers, veteran interiors with a unique smell and a long memory of Commissioners past.

The back of every Met car carries the city’s anxieties in object form: a round Perspex riot shield; an acid kit that is really rubber gloves and a big bottle of water; a first-aid kit and defibrillator; and a throw line for someone who decides to go swimming in the Thames.

I’m the passenger – an operator – for an IRV, our callsign is 41. While my driver makes tea, I go to grab the keys, gently shouldering someone out of the way before they grab the car we want. As I head back to my partner, the dozens of radios around the writing room begin to echo with a voice from Met Command and Control (MetCC)

07:14 - I‑grade, Peabody

“I-Grade now, possible domestic incident on the Peabody Estate, Block C, Flat 28. Sounds of a disturbance heard by the call-taker.”

I wedge myself and my vest into the car’s passenger seat – my driver drives and I try to help with everything else. The clue is in my job title, I operate the radio, read the maps and monitor our call’s updates as they come in on the tablet balanced on my knees. Control’s summary pings through: names, flat number, a neighbour who “can hear shouting”. I ask Control to see if we’ve been there before. I trim the map to what matters — long straight roads with bus lanes as arteries, avoiding the Mayor’s infamous one-ways and the cyclists who will materialise out of thin air at the worst moment.

The driver keeps to his mirrors and momentum, they know what they’re doing. They’ve been on a four-week driving course, I don’t even own a car. But I try to stay at their speed. It is never “the next left” out of my mouth but “the fourth left” and I count them down one by one. Navigation through London's tangle of streets is a challenge; the art is shaving seconds that allow us to safely make progress.

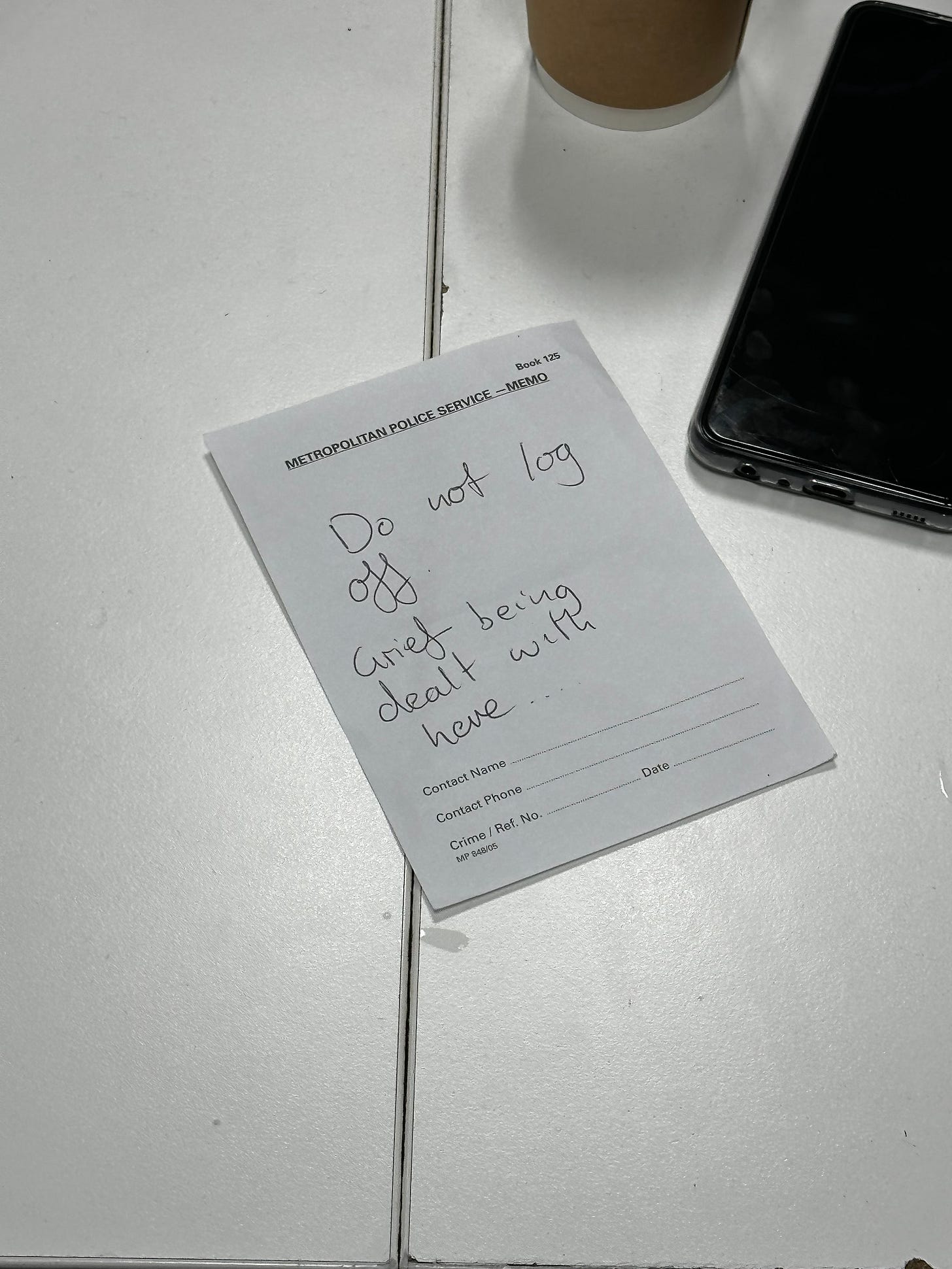

As the blue lights skate along brick and butcher’s tiles, a lone PC on foot gives us a small wave. He’s today’s Diary Car. They go to appointments to take statements or follow up on non-urgent crimes. He’s noticeably without a car — they ran out after briefing — and destined to attend pre-booked grief and weariness by bus and Oyster card.

Those two words are probably the most important in the Met’s book of slang. A griefy call is one that is important but will mean a lot of complexity, drama, and paperwork. A weary one is when police shouldn’t even be there, but where you end up sitting on a sofa you’ve sat on before; listening to a frequent flier tell you about a mean Facebook message from their ex-wife’s sister’s cousin.

We arrive on scene. Estate stairwell with rubbish bags split by foxes’ teeth. It’s always the top floor. Shoes by a thin door. Camera on with a double press. You learn to tune a doorbell like a violin. A Griefy call gets fortissimo until we get in; a weary call gets a single ping that hopes for no answer. This is griefy. The door cracks and a pair of wide eyes appear in the dim hallway.

Even with good notes, a doorway is a curtain. He is pale and loud; she is flushed and small. I start the same way every time: “What’s happened?” It buys ten seconds — long enough to find the children, the dog, any injuries, and the temperature of the air. We separate the voices that have braided together: he gets distance and a chair to talk to my partner; she gets water and a straight sentence about choices and no one gets to stay in the kitchen.

The child on the stairs gets a stuffed dinosaur rescued from under a radiator dripping with the thrown breakfast. I’m forced to play at being a psychiatrist without a degree and a parent without having a child.

No guns on our hips, so authority is posture and choreography. Angles that keep us safe without announcing themselves and can keep a reactionary gap as best as a tiny London council flat can. The baton is there to open letter boxes; all we really have is our voices and hands and if shit really hits the fan there is the orange emergency button on the radio that alerts the whole borough with a heart-stopping tone. In those first twenty seconds of turning up on scene you know whether it will be an arrest, safeguarding, or waiting for an ambulance - or all of the above.

The camera’s red light blinks and beeps like a tiny conscience and, for once, helps. We leave the room cooler than we found it. It turns out it was just an argument that got too loud. It’s formally called a “non-crime domestic”. No offences have occurred – yet, and so we will simply record a risk assessment for our safeguarding officers to check in the morning. The forms begin, child contact reports get sent off to the council, the practical kindnesses that look like bureaucracy until the worst night happens and someone is glad the boxes were ticked. We leave with a plan that will survive until morning, which is often the only honest victory on offer for an officer on a response team.

After a sip of our tea and coffee that have already gone cold, we exhale but then it starts all over again.

The female controller’s voice is already familiar—half chess player, half conductor. “Units for an I‑grade?” is not a question so much as a promise the city expects you to keep in fifteen minutes. “Robbery outside Harrods, suspects just made off, last seen all in black on e-bikes towards Knightsbridge, victim on scene.”

09:40 - Robbery, Knightsbridge

Each borough has its own radio channel, whose voices are the unseen choir of MetCC: civilians and non-operational officers who answer 999, turn panic into coordinates, dispatchers who talk to us and a controller who grades chaos into I (now), S (soon), E (eventually but probably never). The best call‑takers keep people breathing on the phone while turning panic into coordinates and verbs. You live inside that cadence. You also learn the physics of keying up fast; hesitate and you’re cut off mid‑call sign by someone keener.

I grab the radio and assign us. There’s a small pride in pressing the button first, a smaller guilt when you can’t. Resources are thin: two boroughs, hundreds of thousands of people, one police station and one response team sometimes barely into double digits of officers some days. Just a few years ago the same area had six response teams operating out of six police stations, but that was before the cuts.

We’re too late to catch the robbers. Sirens help, but an e‑bike can cross London while we’re still parting a sea of traffic. The victim has a sore arm and a missing £130,000 Patek Philippe. The Area Car roars past in a vain attempt at a search. We focus on the report. He’s visiting from the Middle East. “I love London,” he tells us, “but it never feels safe any more. This wouldn’t happen in Dubai.” We apologise and take swabs from his wrist in case any of the suspect’s DNA remains. CCTV shows two men in black on black bikes. Not much to go on. We leave the report in the Robbery team’s tray, not that they will have time to investigate it.

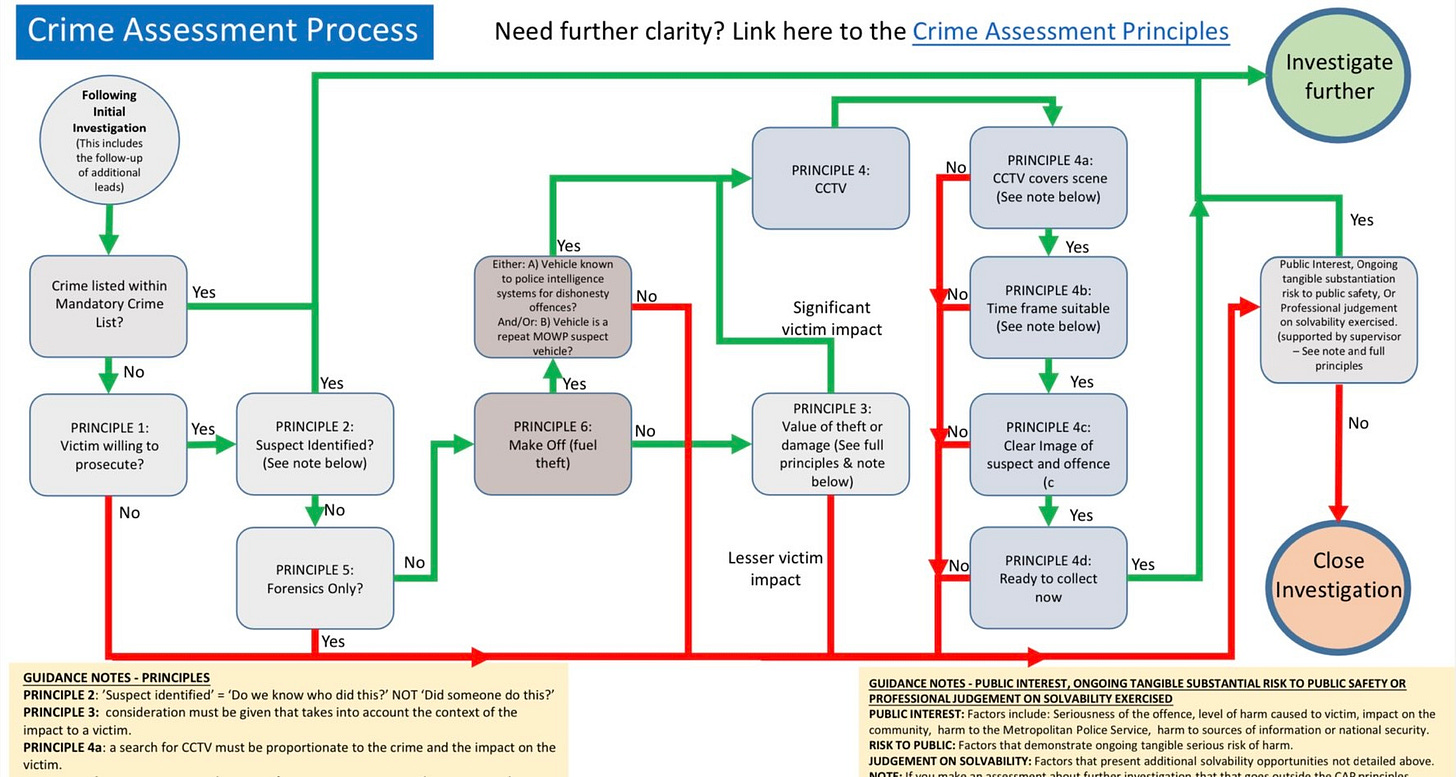

Response officers conduct what’s called the “primary investigation” for every incident they attend - they take an initial report, ascertain if there’s any leads and look for camera footage and if it requires further investigation, off it goes to the relevant specialist detectives. But very little makes it to those teams.

We are issued a flowchart and almost every path on it leads to closing the investigation. Victim not interested? Close it. Value of the theft below £100? Assessed out. No CCTV available to collect right now? Don’t even bother, just give them the crime number and go back to work.

11:00 - Welfare, St Mungo’s

“From Met Control – we have an S-grade, welfare check. Caller is the subject’s sister. Last contact last night. Has not been answering his phone. Currently staying at the St Mungo’s hostel. LAS holding calls and unable to attend at present.”

All the Pandas are busy with their own grief, it’s just us left so we go. Not all our calls are crime. Many are crises with administrative clothing. The LAS are the London Ambulance Service and are equally short-staffed, with much of what they can’t handle left to the Met.

The police have become Britain’s social service of last resort, dropped into people’s worst five minutes with no backstory and every expectation to fix things.

No blues or sirens for this one though —S is soon, not now—but we make progress where we can. I ask Control for any previous attendance; there are three reports in the last year, one with a note about medication and missed GP appointments. I’m also warned our subject “flashes Mike Hotel” - a code for mental health issues.

Hostels, halfway houses, asylum hotels, they’re all the same. A terraced Victorian house in a nice part of town knocked into a multiple occupancy dwelling with a couple of dozen bedsits for society’s most vulnerable and watched over by a receptionist who spends their shift on all-day-long video calls back home. The stairs smell of last night and are sticky. The top floor again.

We knock as if waking a friend. “Police. Not here to arrest anyone. Just checking you’re alright.” Nothing. Telling Control it’s an “NRRK” would be the easy result - No Reply, Repeat Knocking, move on – but the notes say previous attempt, so we buy a few extra minutes from the clock. I call the sister; she’s crying quietly in Leeds and says he hasn’t answered texts since midnight.

A shuffle. The door opens. A bedsit with too much sky in the window. The floor is more belongings than carpet. A mattress for a bed. We stand by a sink that’s been full for weeks. A stack of NHS letters, unopened. He lights a cigarette and tells us he’s missed his depot injection and feels low but won’t kill himself — and you learn to know who means it. He lights another cigarette and makes clear he doesn’t want an ambulance and definitely doesn’t want hospital.

Sometimes there isn’t much we can do. He’s alive, he isn’t about to harm himself, and he knows where help is. Another safeguarding report, numbers swapped with the hostel, and we’re back to the road.

The morning goes Q — we never say quiet — as people start work or school and the crackheads are yet to wake up. We swap life updates with another unit at the gates of Hyde Park and tell the kind of jokes that keep the edges soft.

Another S‑grade comes out — a weary neighbour dispute about a fence in Kensington. Radio silence. No one volunteers like they did for the robbery, they know it will be what we call an LOB – Load of Bollocks. Then the dreaded roll call through the callsigns from the Guv’nor begins - he needs someone to go. 81 are tied up at hospital; 82 are dealing with some problematic Irish Travellers; and 83 are sitting next to us and very much available. We grin in sympathy as 83 peels away into the sunset, not to be seen again for the rest of the shift. “Gone but not forgotten,” I say to my driver.

12:45 - I‑grade, Uxbridge Road

On the car’s other radio we’re tuned to the neighbouring borough’s channel in case they need help. They do. “I‑grade, males fighting outside Ladbrokes on Uxbridge Road, weapons involved.” Silence. Their units are all busy and it’s not even 1pm. The Diary Car offers but it sounds on the radio like he’s on a District Line train. Their skipper gets on the radio: “Send it to surrounding channels, please.” When it lands on ours, we offer. It’s just us. “It’s on the way to your box (the in-car tablet) now, 41. White male with a bottle, last seen outside Ladbrokes.”

Blue lights through traffic, crossing from one borough to another. We hope the fight will be over before we turn up and it will be what the Met call an ASNT (Area Search, No Trace) but which veteran officers term an ATNS (Area Trace, No Search) . Outside the betting shop, two men circle each other while hundreds walk by as if it isn’t happening. Broken glass glints on the pavement. I’m out before the car fully stops but my driver carries the Taser; I wait half a beat and give the only order that matters to the one with the bottle and the ripped shirt.

“Put it down. Get back.”

He hesitates. That heartbeat is longer in the retelling; in the moment it’s a coin flip. My driver is out now, Taser drawn. Two red laser dots quilt the man’s sweaty chest. The bottle hits the ground. We move in. Wrists, cuffs, click, lock. Choreography; ugly, practised. It was unprovoked; the victim wants to make a report. I tell our new friend who stinks of beer that he’s under arrest for assault and possession of an offensive weapon.

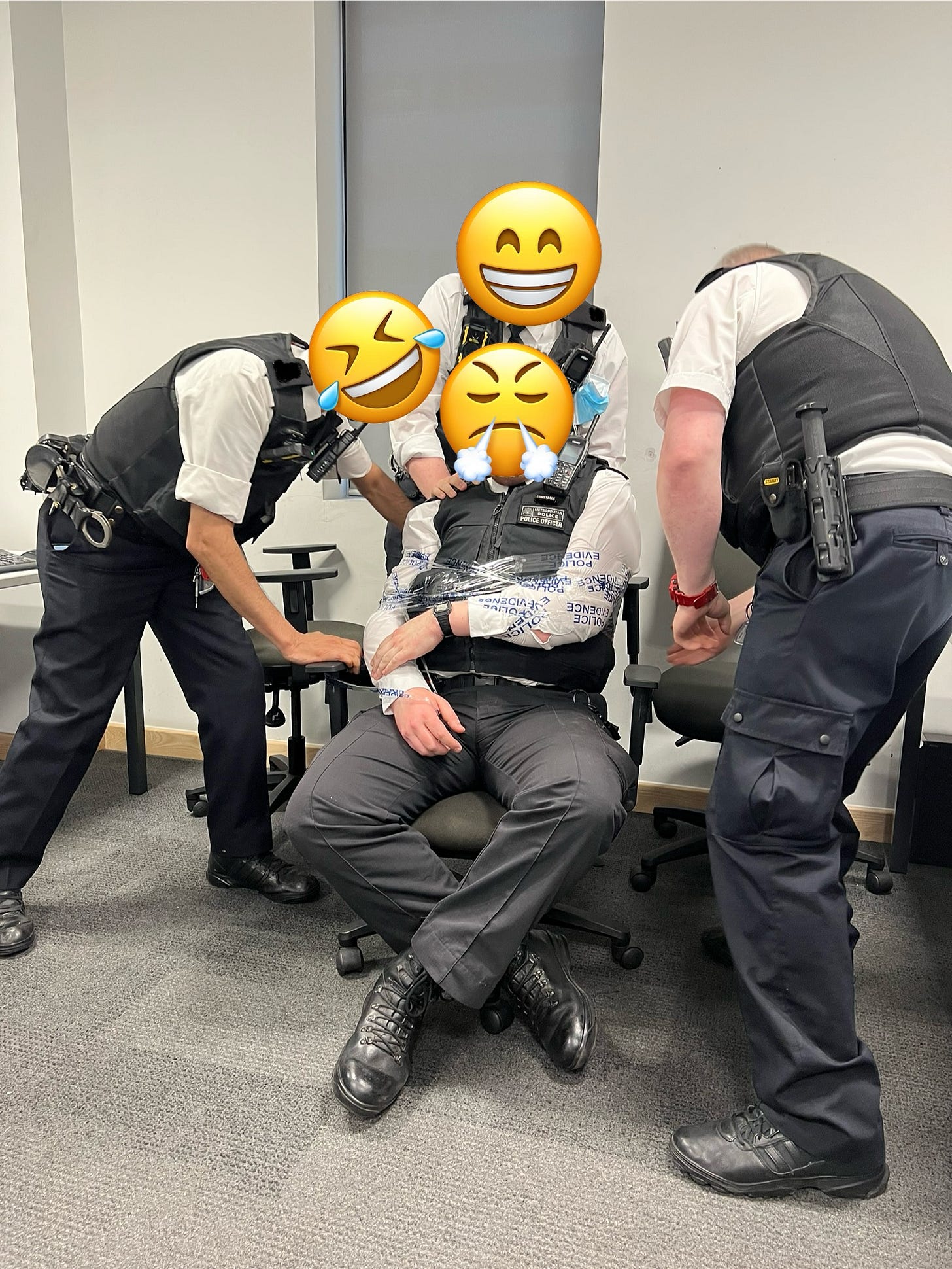

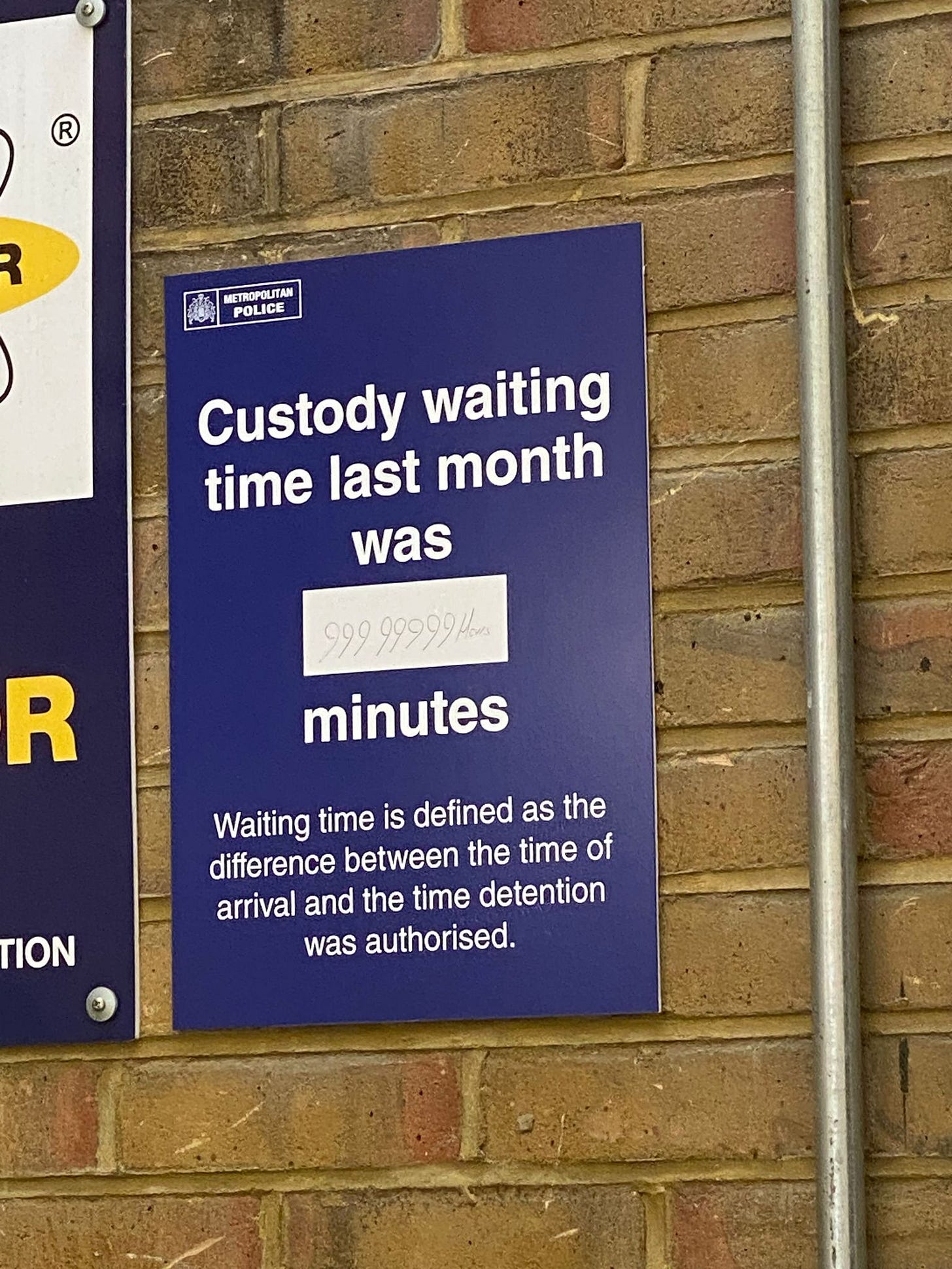

Then comes the van. A Ford Transit with a prisoner cage built into the back. My partner stays to get statements and CCTV footage while I hop in the van and a ride to a custody suite follows. The old days of cells in every station are long gone; now prisoners travel across London to one of the few remaining custody suites. Our usual custody suite is closed as the cells are “too cold” and I am sent south of the river to a station I’ve never been to.

There’s usually a queue of vans in these stations’ yards, a conveyor belt of the morning’s mistakes. When we get to the front, a custody sergeant appears with trademark sceptical eyebrow. Officers believe that most custody sergeants think putting prisoners in their cells is a major inconvenience.

After a search, I explain the arrest to the custody skipper. She’s seen it all before. She sits on a podium with several other sergeants, each booking in a prisoner of their own and hearing accounts from officers. I’m in a clearing house for London’s detritus. Most in this custody suite are already well-known to police and are on their nth chance at redemption — which has once again ended with the harming of a fellow citizen and is marked simply by a opening a new page in their custody record.

I get a barrage of questions from the sergeant and the prisoner answers a risk assessment about their mental and physical health, but eventually detention is authorised. He’s then placed in a cell and twenty-four hours begins counting down. For the new prisoner it’s time for a nap and a microwave meal but for me it’s only the beginning. Due process is slow on purpose—and painful by accident.

I get a ride from another van and meet my driver back at our station, he grabbed us Nando’s on the way and we get to work. This will need a crime report, a case file and other assorted paperwork.

15:00 - CONNECT

Paperwork means using CONNECT. CONNECT is the software that was meant to stitch the job together and instead unpicked hours from our lives—dropdowns that lead to more dropdowns, attachments that won’t attach, a clock that eats afternoons and a save function that sometimes deletes entire reports. The adrenaline of the arrest crash lands like a wardrobe. It steals time and willpower so effectively you wish you were dealing with a mental health crisis two streets over. CONNECT is so hated that statistics show a decline in arrests after it launched, so desperate were cops to avoid using it.

We tap like birds at our keyboards as our colleagues return their cars and Tasers, waving us goodbye as they go to the pub down the road. We promise we’ll join them but we know that’s unlikely. Even the Diary Car leaves before we do, the No. 11 bus having got him back in one piece. The irony isn't lost: the officer without a car gets home before the ones with blues and twos.

17:00 - Handover

I press submit and we both sit there praying as the wheel on the screen turns and turns. It freezes for a moment. “Don’t you dare,” both of us mutter in sync.

It then spits out a case number; CONNECT has grudgingly accepted our digital offerings and we make our handover to one of the Late Turn skippers. They’ll get our prisoner interviewed and charged. As we head for the locker room, the voice once more speaks to the writing room.

"From Met Control, units on the I-India Grade now..." But it's not for us. We slid the batteries out of our radios hours ago, we're finished and if we hurry we can still make team drinks. We step over a homeless man sleeping by the front counter when we leave, while the stressed station officer attempts to take a Chinese student's phone theft report through Google Translate.

Tomorrow the radio will crackle and someone will be the first to the doorway. Cuts or no cuts, London dials 999 and someone goes.

Absolutely loved it. Thanks for sharing

Ned I'm only part way through but you've nailed it. Brilliant piece, full of colour. I haven't been in response in over twenty years but you brought it all back. Great piece of writing.