All We Can Be Is Tourists Now

Last month, a video went viral showing a queue of climbers in puffer jackets waiting to reach the summit of Mount Everest. The poster described it as: “A DMV line at altitude for really rich people.”

For most of humanity’s history, our tallest mountains have been in realms entirely separate from those on earth. In ancient times, gods were believed to reside on these peaks.

On the summit of Mount Everest is said to live Miyolangsangma, the Buddhist goddess of inexhaustible giving. The idea of gods hanging out up there is not absurd, given that it was physically and technically impossible for anyone to reach such summits until recently. Mount Olympus, believed to be the home of Zeus and his family, wasn't summited until 1913 and it wasn't until 1953 that Tenzing Norgay and Sir Edmund Hillary reached the peak of Mount Everest.

The expedition Sir Edmund took part in was the culmination of years of planning and required the efforts of hundreds of porters and staff all to support just 10 climbers. This ancient perception of these peaks as sacred spaces contrasts sharply with today's reality. In 2019, a record-breaking 891 people trampled through Miyolangsangma’s palace, with some days seeing over 200 climbers attempting the summit.

Beneath these explorers’ layers of North Face jackets are, without any ill intent, some rather ordinary people. The typical Everest climber today is not the intrepid explorer of yesteryear but rather a wealthy amateur with a penchant for adventure.

The average climber is 44 years old and spends between $30,000 and $100,000 on the expedition. This shift has brought in a new demographic that views Everest as a status symbol rather than a sacred challenge. Wealthy surgeons from places like Sioux Falls in South Dakota will join Wall Street investment bankers in booking their annual leave with HR to climb Everest and once returned, the fact will likely become one of their most often repeated anecdotes for the rest of their lives.1

Watching the video reminded me of a remark by Sir Wilfred Thesiger. Sir Wilfred Thesiger, a British explorer and writer born in 1910 and known for his travels in the Arabian Peninsula and Africa. All along the way, he took both mesmerising photographs and wrote several books. In 1999 he spoke to the Washington Post and said something that haunts me:

“The biggest misfortune in human history is the invention of the combustion engine. Cars and aeroplanes diminish the world, rob it of all its diversity. Young men who meet me want to know how they could do what I've done. But all they can be is tourists now.”

Take for instance our imaginary surgeon from South Dakota who wants to climb Everest. A quick search on Google Flights tells me that he if drove to the nearby Sioux Falls airport on Monday after work, he’d be able to get an American Airlines flight to Dallas at 7pm that evening. He’d then be able to catch the 11pm Dallas to Doha Qatar Airways flight landing the next evening.

After a short layover in Doha, he’d be able to catch another Qatar Airways flight and be in Tribhuvan Airport in Nepal just less than 100 miles from Mount Everest on Wednesday morning. A 30 hour journey across the world, all for the price of $1,000.

The aeroplane has destroyed the concept of distance for us in the way that motor cars destroyed the concept of distance for people of Wilfred Thesiger’s time.

It is obviously undeniable that in the same period of time as distance’s destruction, humanity has seen history’s greatest increase in quality of life and development by any reductive measure. But as the famous French criminologist Edmond Locard taught us, “Every contact leaves a trace.”

In 2001, just two years before he died, Sir Wilfred gave a television interview in his nursing home which can still be watched on YouTube. In it, with shaking hands and a quiet voice he reflected further on the shrinking of the planet over his lifetime:

The world has now been diminished completely. There is no variety anywhere. You go off to the Congo and in the forest will find an advertisement for Coca Cola.

It is not just speed and distance. I've found that the influence of globalisation and modern transportation has made its mark on our experiences no matter the destination.

I recently travelled to San Sebastián in Spain with two friends Nick and Zach. Nick is a coffee obsessive and you can put him in any part of the world and he will be able to find what he calls a speciality coffee shop.

I have been to several countries in every corner of the world with Nick and as a result to several of these coffee shops, and they are all exactly the same. On walking through the door, whether it is in a dingy Chengdu street or a quiet corner of Beirut, you enter a consulate of coffee hipsters.

Minimalist design with climbing plants adorn the sidelines as baristas in Carhartt workwear dial in their grinders to ensure your ‘Kiwi Bikini’ drip coffee is as good as it can be.

These shops are meant to be manifestations of a rejection of the “second wave” of coffee and its chains like Starbucks but in reality they are just as homogenous as what they rebel against, outposts of western culture in remote corners of the world. For tourists it allows them to feel at home and for locals it lets them replace their culture with a global one. For Nick it’s joyous, for me it’s depressing.

The ubiquity of specialist coffee is just part of the substitution of experiences in place of travel. In a world where journeys that took even our ancestors weeks of planning and months of travel, being able to accomplish the same with a click and a short flight prevents us really from being able to travel at all.

It feels unfair to gatekeep our imaginary surgeon from Sioux Falls from doing what he wants, but it should be up to us to actively cultivate a sense of awe and an appreciation for the unknown. We have been so successful as a human race that we have made so much not only easily achievable technologically but also affordable.

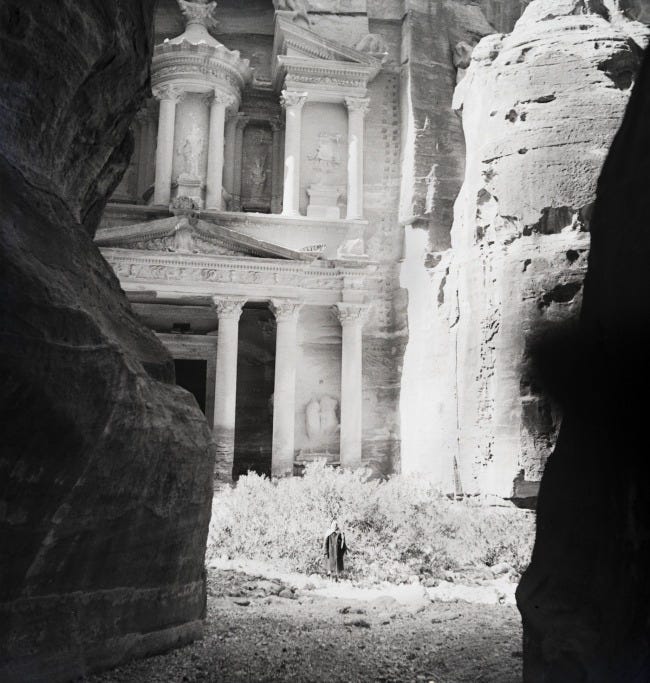

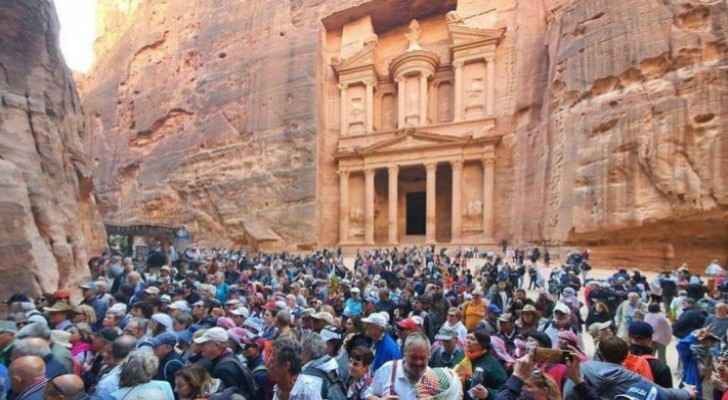

Petra, the ancient Nabatean city in Jordan and a wonder of the world, was once lost for almost 2,000 years. Now, just two centuries on from being discovered by a wandering Swiss explorer, it can be accessed by anyone able to pay the £52 that a WizzAir flight from London to Amman costs.

Since Petra’s rediscovery in 1812, tourist numbers have grown exponentially. In the early 1900s, only a handful of intrepid travelers visited the site each year. Today, it welcomes more than a million visitors annually.

In the shadow of the famous Treasury you will find crowds of tourists being shepherded into the ideal spot to immediately take the best photo to inform their Instagram followers. Petra has always been a place for travellers, having become wealthy as a Silk Road hub, but it was just a small part of a long and treacherous journey.

I am glad so many can see the beauty of Petra but its transformation from a lost city to a mass tourism destination is a stark example of how increased access and commercialisation have changed the nature of travel.

Thesiger himself only explored Arabia because he was disgusted by what he saw as the modern world in Europe. However, unlike in Thesiger’s time, there are no corners of the world left to find and few places for anyone of his mindset to escape to other than totalitarian hermit states like North Korea or Turkmenistan.

Something fundamental has been lost in the process of travel. The experience is safer and more accessible but the thrill of setting out into the unknown, of immersing oneself fully in a new culture and way of life, has been replaced by a superficial sampling of experiences.2

For instance in Indonesia you can spend time with the Mentawai people, an indigenous tribe who from photos posted on social media by intrepid travellers appear to wear loincloths and live on an island like the uncontacted tribes last seen in your parents’ faded copies of National Geographic.

At first glance it would seem that despite my complaints, there really are cultures still out there that exist for themselves as opposed to the eyes of outsiders.

Instagram captions describe the Mentawai as one of the planet’s “last hunter gatherer tribes.” One visitor even proudly said online that during the trip he felt it was like “living thousands of years ago” and that he met a shaman who revealed the tribe do not even know about the western concepts of polyester or even sexuality. Remarkably, however, they do know about the western concept of websites and advertise an “immersive experience” for just $500 per person on theirs with an included “photo session.”

With no hopes even in the remote islands of Indonesia, I remain curious as to where and under what conditions we can actually travel somewhere and not be tourists? Please do get in touch with any recommendations by emailing or by commenting on this post.

In 1938, my grandfather got a job in East Africa working for the oil company Shell. It took him two weeks to travel from London to Mombasa, calling along the way at Marseilles, Malta, Port Said, Suez, Port Sudan, and Aden. Aged 22, he was due to be out there for three years and would have been unlikely to see Britain before then. Half a century later he reflected on that journey out to Africa in his book Going Solo.

Nowadays you can fly to Mombasa in a few hours and you stop nowhere and nothing is fabulous anymore.

Nothing is fabulous anymore, all we can be is tourists now. But at least we’re tourists with good coffee.

What I’ve been reading:

A Kind of Anger - Eric Ambler: As many of you know, I am partial to a vintage crime thriller. This 1950s story weaves in tales of sensationalist magazines and washed up journalists hunting the ghosts of Arab spies and American conmen in glamorous European settings.

Coast to Coast - Jan Morris: Written just after accompanying Sir Edmund Hillary’s Mount Everest expedition, this tells a story of an America that no longer exists and is simply really good fun.

In fairness, it is not without danger. Climbing Everest still has about a 1 per cent death rate – but this is largely due to the demographics being made up of amateur climbers who are often older and in less than peak fitness.

Thank you to M.S. for allowing me to steal this sentence in return for this footnote.

I went to Kyoto in the spring, for the first time since the pandemic, and the transformation from previous times I've been there was astonishing. Kyoto has always had a lot of domestic tourism, but a post-covid resurgence and the addition of a lot of foregin toursts seems to have tipped the balance. The central bits and some of the couple of high profile sites I went to were utterly rammed, to the point of being unvisitable. It's tricky because I have no special right to the city and in a sense it is great that more people get to see what are fantastic historic places, but it really feels like no one is really experiencing them beyond a very shallow postcard picture.

What I would say, is that the drop off in traffic from the 5 or so most famous sites to the next set of (frankly equally historic & significant & beautiful) places was amazing. Over in the west side of town there was no sense of tourism at all, and plenty of amazing temples were very quiet. I think that there is a sense that the Instagramization of travel has given us all much wider horizons, and yet we all end up going to the same limited number of places.

There is at least one kind of place you can travel to without being a tourist. A war zone.