Why was Britain freeing slaves in the 1960s?

You’re reading my newsletter, Terra Nullius, on the weird and interesting intricacies of the countries and places that make up our world. It currently goes out to around 1,000 people every week. You can subscribe here:

When I visited Oman for the first time several years ago, I visited the Al Alam Palace in Muscat, the capital city. At the gates of the Sultan’s ceremonial residence, I was told a fascinating story about the place by an Omani friend.

Until the 1990s, when it was demolished to expand the palace, the British Embassy was right next door. The Embassy’s compound for many years featured a large iron stump used as a turning point for parking cars. Newly appointed diplomatic staff were often bemused to learn that this plain old stump in the courtyard was held in reverence by some locals for having played a very important role in their lives.

The stump had once been the base of the Embassy’s flagpole, flying the Union Jack for about a century. It was also where hundreds of slaves gained their freedom.

Since Britain abolished the slave trade in 1807 a tradition developed, the origin of which is slightly unclear, that any slave who touched the British flag would immediately be free and granted protection from future slavery by the King or Queen of the time. As flags can sometimes be quite high up, this legend evolved to allow someone to instead touch a flagpole and receive the same magic effect.

In countries where slavery was not abolished, escaped slaves or those who had been ill-treated by their owners would hear of this legend and find their way to the nearest British diplomatic post and its flag.

Having touched the flagpole, an official would then help the slave sign or put a thumbprint to a statement formalising a request for freedom.

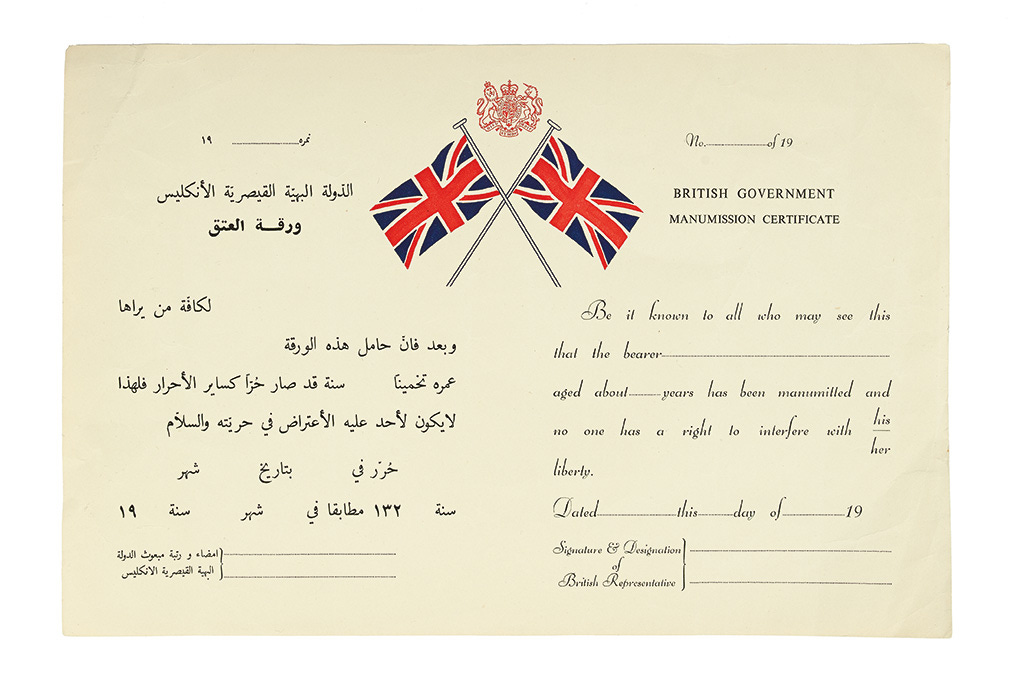

Once inked, the now ‘manumitted’ (freed) slave would be granted a certificate signed by a British official that declared in elegant copperplate that “No one has a right to interfere with his or her liberty.”

While the countries where this took place tolerated slavery, Britain’s influence and power made it very difficult for governments to prevent the individual manumissions given by diplomats. Trying to recapture a freed slave under British protection could lead to a diplomatic incident.

The touching of flagpoles went on well until the latter part of the 20th Century, with Britain issuing the last manumission certificate in 1964. In the year the Beatles released Twist and Shout and A Hard Day’s Night, the British Consulate in Muscat gave 13 slaves their freedom, while their counterparts in Dubai freed 16.

The British Government worked hard to eradicate slavery in its Gulf protectorates and allies. Kuwait declared the practice abolished in 1949, Qatar in 1952, while six of the seven Arab Emirates followed in 1956, Abu Dhabi doing the same in 1963. Saudi Arabia outlawed slavery in 1962, with the two countries that made up Yemen following shortly after.

For most of the slaves freed, the manumission certificates were their only legal documents or proofs of identity, and they would often end up as de facto passports. For many years, recipients would appear at British Embassies in the Gulf with requests for replacement certificates once the front and back had been filled with visas and border stamps.

The only remaining holdout in the region was Oman under its conservative Sultan Said bin Taimur, who refused to follow his neighbours in abolition. In archival papers, the genesis of the practice of manumission is discussed by Sir William Luce, the British Government’s Chief Political Resident in the Persian Gulf:

We cannot trace any agreement on which our exercise of the function is based, and assume that it is simply one which we arrogated to ourselves in the past by virtue of our special position.

Sir William went on that given how obscure its origins were, the right should not be given up without at least trying to force the issue in Oman, but the Foreign Office did not have much success. The UK and Oman instead reached a compromise in 1964 that slavery would not be abolished, but if a slave asked for his freedom from their local governor then it would be immediately granted.

Just a few years later in the ‘Renaissance’ that followed the accession of Sultan Qaboos bin Said to the throne of Oman in 1970, one of the very first actions of the new Sultan was to formally abolish the practice entirely. With Sultan Qaboos’s declaration, the Persian Gulf was finally free from legalised slavery.

If you’re enjoying this newsletter, please share it:

Acknowledgements and References:

One of the most illuminating places to learn about this issue was at Bin Jelmood House, part of the Msheireb Museums in Doha. In 2019 I visited this house, dedicated to the contribution and sacrifice of enslaved people, and thoughtfully confronts how they helped Qatar evolve from its humble origins into one of the world’s richest countries. If you ever find yourself in the city, I highly recommend a visit. (Link)

Writing this would have been impossible without the fantastic resources of the Qatar National Library’s Digital Library (Link)

Finally, I am grateful to Hugh Arbuthnott for his book British Missions Around the Gulf 1575-2005 for his great detail on the flagpole in Muscat.

Whenever I mention to the modern-day version of leftists how recently many Islamic countries had legal slavery, they always retort that it was "just some musty old law on the books, there weren't any actual slaves in those countries in the 20th century". They also like to talk a lot about European imperialism, and are ignorant that up to 1913 the Turks ruled significant parts of eastern Europe; and it was not a benevolent rule..

This essay is fascinating, the story of the flagpole stump is astonishing…thank you for a brilliant Sunday morning read.