When Countries Get Divorced

You’re reading my newsletter, Terra Nullius, on the weird and interesting intricacies of the countries and places that make up our world. It currently goes out to around 1,000 people every week. You can subscribe here:

Did you know Czechoslovakia still exists? Not only that, but almost 30 years after its supposed demise, the country is entirely located on the corner of a private street in Britain.

A couple of years ago, I walked around London with my friend Ido as part of an event called Open House. Open House is a weekend where buildings normally closed off to the public are thrown open, government departments, embassies, etc. Ido has a bizarre fascination with brutalist and modernist buildings, so we visited the famously brutal Slovak Embassy.

The embassy is on Kensington Palace Gardens, a street owned by The Queen in west London that is home to some of the world’s richest people and various foreign embassies and diplomatic residences. The Slovak Embassy stands out on a road of otherwise elegant period buildings or pastiche equivalents. Properties start in the tens of millions, are sold on 100-year leases from the Crown, and come with guaranteed privacy as the road is closed to non-resident cars and photography is banned.

Walking around the embassy, we learnt a fascinating story that would be familiar to anyone who has been through a divorce. Czechoslovakia was formed for the Czech and Slovak people in 1918 out of the Austro-Hungarian Empire following the First World War. By 1933 it was the only democracy left in central Europe and was targeted by its authoritarian neighbours, with parts of Czechoslovakia annexed by various countries until March 1939 when there was none left, and it ceased to exist.

After the Second World War, Czechoslovakia was re-established almost exactly along the lines of 1918. In 1948, Communists took power in the country, and the country became a satellite state of the Soviet Union; and in 1960, it was renamed the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic.

Later that decade, the London embassy for the country was built. Three Czechoslovak architects designed the striking concrete building. At the height of the Cold War, such a building was a political statement. Allowing London residents a rare chance to see a projection of the Eastern Bloc aesthetic and architectural style. The building was also a power projection for a state that was active in espionage in the UK. Czechoslovak spies acted with impunity in Britain during the Cold War and it was Czechoslovakia that the British MP John Stonehouse was secretly an agent for.

Towards the end of the Cold War, much of the satellite Soviet Union experienced significant changes in 1989, Czechoslovakia went through the Velvet Revolution and the socialist government was outed. In 1992 the newly democratic country decided to divide the country into two new independent entities: The Czech Republic and Slovakia.

But how do you divorce a country that has existed for almost a century? When most countries split up or reform, there is a formal successor acknowledged by the international community. That successor state can then maintain its predecessor’s continuity and take its seat at the UN, diplomatic properties and so on. For instance, Russia is considered the successor of the Soviet Union, while the five states that made up Yugoslavia agreed to split up the role fractionally.

However, with Czechoslovakia, neither the Czech Republic nor Slovakia laid claim to continuity and began completely fresh. But they did have to work out how to divide up their old country’s possessions. The two countries agreed that all possessions would be divided two to one, which is the same as the ration between the Czech and Slovak population. This ratio was adopted with everything, from bullets for guns, trains, and even gold reserves. Real estate was considered owned by which of the two new countries it sat in, but what about embassies abroad?

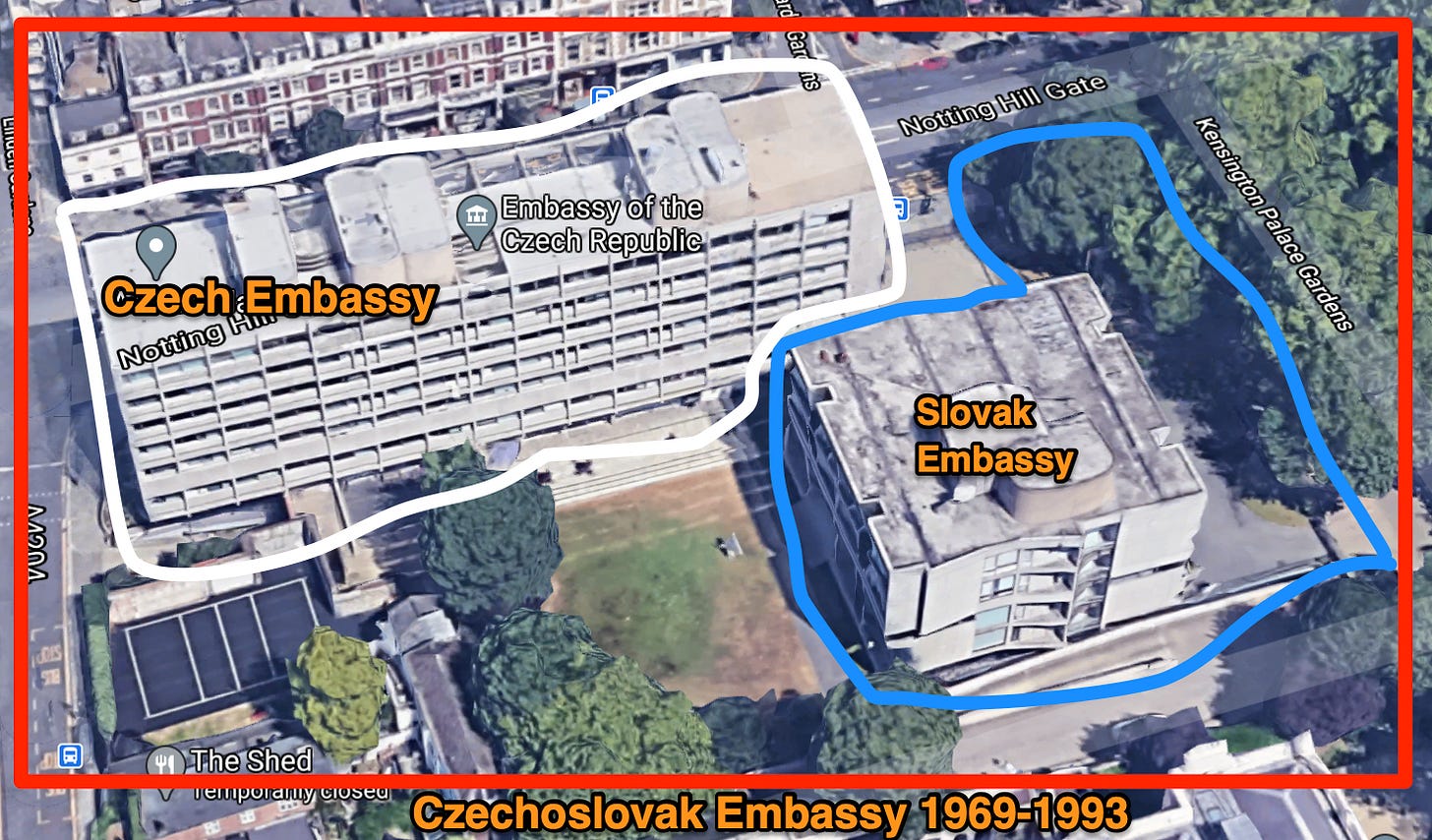

As my very crude diagram of the former Czechoslovak compound in London shows, they got divided two to one as well. From my memory of the tour, the garden is shared and a common smoking area for both nations - but I could be wrong.

The problem is, no one seems to have told the Land Registry about the division. When researching this newsletter, I obtained the latest property deeds for the compound above. I was hoping to see where the exact demarcation line is and when it happened. Instead, the UK Government’s official register of property ownership records the following as “Current as of 15 March 2021”:

Registered Owner: The Czechoslovak Socialist Republic of 25 to 30 Kensington Palace Gardens, London W8.

So while the pandemic prevents us from travelling abroad, you could at least take the Number 94 bus to see a country that’s not supposed to exist.

If you’re enjoying this newsletter, please share it: