The Country That Ran on Cocaine and Yoga

Hush. On the threshold of the forest I do not hear words you call human, but I hear newer words spoken by droplets and leaves far away.

- Gabriele d’Annunzio, La pioggia nel pineto (The Rain in the Pine Wood)

As naval shells exploded amongst the terracotta tiles of Fiume’s roofs, throwing red dust and debris across his little Adriatic paradise, Gabriele D'Annunzio likely wondered where it had all gone wrong.

Just one year before the Italian poet, aristocrat, and soldier had created what he thought was Utopia nestled amongst the blue shallows and rolling green hills of what is today the Croatian coastline. His country had been born of the chaos of the aftermath of the First World War and the disintegration of the empires that had for centuries made up the old world of Europe.

When the war began, Italy had been neutral but in 1915, the King of Italy had been convinced to join in the war against Germany and her allies and so signed the secret Treaty of London with Britain, France and the other members of the Entente. In return for Italy’s support, the Entente would ensure, if victorious, that the Italians were handed much of what was the Austrian coast on the Adriatic. Other Austrian land would, by the treaty, be set aside to create an independent kingdom for Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes - later Yugoslavia.

Forgotten Fiume

However, the little city of Fiume was not mentioned in the treaty. Fiume was a port on the Adriatic Coast with several thousand residents, almost half of whom were ethnic Italians that had been under Austro-Hungarian rule for several hundred years after it once having been a Venetian trade port. By some quirk, Fiume was missed in the Treaty of London, probably because it had never been envisioned by the Allies that the Austro-Hungarian Empire would ever truly disintegrate and the rump of it that would remain required a sea port in some form. The city’s other residents were ethnically Serbian and Croatian, who knew the city as Rijeka (as you will find it named on a map today). All of this complexity meant that the fate of Fiume became a major topic of controversy during the Versailles Peace Conference. President Woodrow Wilson had become so unsure of what to do that he proposed the place become a free city and the headquarters of the nascent League of Nations, under the jurisdiction of no country.

By September 1919 there was still no conclusion as to the fate of Fiume. Events had overtaken the place and through the Treaty of St Germain, the Austro-Hungarian Empire had been dissolved after the abdication of the final Habsburg Emperor Charles I. Once again, Fiume had not been mentioned in the treaty and the country it had been set aside for no longer existed. The city’s fate was still at play.

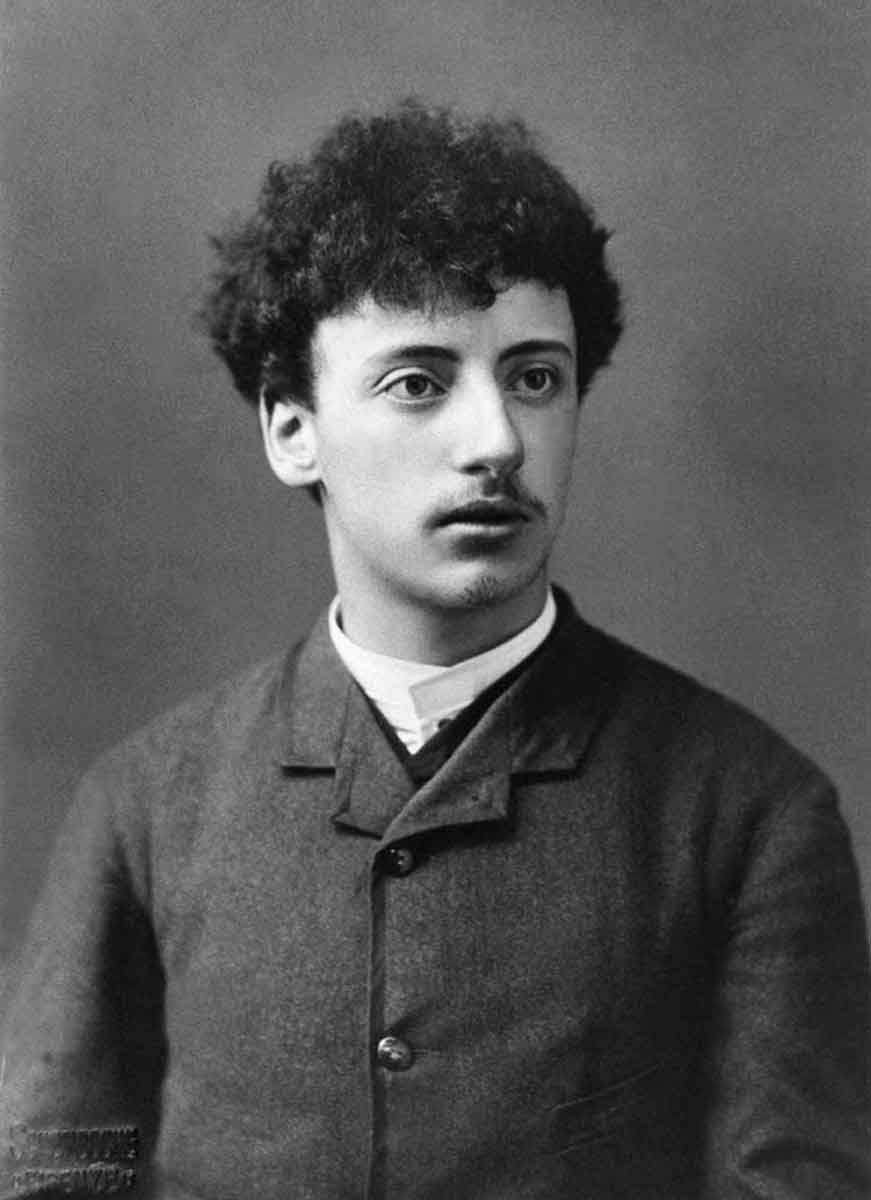

Enter Gabriele D’Annunzio, an aristocrat from Abruzzo on the eastern coast of Italy. Born in 1863, he was a handsome and intelligent child and was nurtured by his family to be exceptional, with a predictable side effect of immense selfishness. As a teenager, he had begun to dabble in poetry and it was praised by authors unaware of his age. At university he began to be associated with Italian irredentism, a philosophy that yearned for all ethnic Italians to live in one country – by retaking places under foreign rule like Corsica, Malta, Dalmatia and even Nice.

He began to be published as a writer, starting with novels that were soon forgotten and largely inspired by other European authors. In fact an early 20th Century edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica rather scathingly states the novels had “little fundamental originality.” But as he grew older he began to transition to poetry, and Italy began to pay attention and he would end his days as the most revered Italian poet since Dante. That same Encyclopaedia Britannica entry, that so rudely described his novels, says of his poetry that “he opened up the closed mine of [Italy’s] former life as a source of inspiration for the present and of hope for the future, and created a language … a thing of intrinsic beauty.”

His poetry was heavily dominated with patriotic and classical tendencies by taking on inspiration from poets like Ovid but transferring them into the modern age by imagining bucolic Italian countryside filled with modern farms connected by telephones and filled with other exciting technology. He sought a futurist Roman Republic where all Italians were united under one flag to live out his ideals. It was not for no reason that Mussolini would later commission a biography of D’Annunzio that called him the “John the Baptist” of Italian fascism.

Not content with being just a literary hero, he also became a war hero during World War I. Having encouraged Italy into joining the conflict through his writing, he later joined the Royal Italian Army before training as a pilot and losing an eye while flying seaplanes. Late in the war he is famous for leading 11 aircraft from Italy across the mountains to Austria where they dropped 50,000 leaflets over the city of Vienna in a propaganda raid. The leaflets had been written personally by D’Annunzio but curiously had not been translated into German for their readers. If the recipients had been able to read them, they would have read the heavy patriotic style he had become famous for before the war:

“On the wind of victory that rises from freedom's rivers, we didn't come except for the joy of the daring, we didn't come except to prove what we could venture and do whenever we want, in an hour of our choice ...The rumble of the young Italian wing does not sound like the one of the funereal bronze, in the morning sky … Long live Italy!”

In addition to the 'Flight Over Vienna,' D'Annunzio led the 'Bakar Mockery.’ Long before the war, D’Annunzio had become obsessed with the machines of war, and was particularly obsessed with torpedoes. In a characteristically overblown operation, the poet took several torpedo boats in 1917 into an Austrian bay on the coast of modern-day Croatia and evaded coastal batteries and patrols to be able to get more than 80 kilometres inland. Eventually, D’Annunzio and his ships reached their target and let off six torpedoes, with only one scoring a hit and scratching a freighter. The Italian flotilla quickly fled and it ended up being turned into a great propaganda victory and by the end of the war, D’Annunzio had been showered in medals and decorations.

In adulthood, his childish beauty had disappeared, the boyish curls replaced with a bald head atop a skinny frame and marked out by appalling teeth. His wartime blindness was coupled with a poor constitution that left him often ridden with fevers. His biographer Lucy Hughes-Hallett writes that one observer described D’Annunzio as “a dwarf of a man, goggle-eyed and thick-lipped, truly sinister in his grotesqueness, like a tragic gargoyle.”

With the war over and peace supposedly beckoning for Europe, this tragic gargoyle needed a new focus and that was Fiume. It would, D’Annunzio said, be a “searchlight radiant in the midst of an ocean of abjection.”

The Regency of Carnaro Arises

During the negotiations over the city’s future, the Italian government was not prepared to take any proactive action to annex the city and it would almost certainly become part of the new Yugoslavian monarchy. In the meantime it had been garrisoned with troops of the Entente, led by Italian officers.

The Italian government’s lack of interest was unacceptable to D’Annunzio and he made clear he would take action to prevent it becoming part of Yugoslavia by default. With his fame and pedigree he was able to quickly assemble a small private force of ex-soldiers, who he quickly took to calling his “legionaries'. In September 1919 after the Treaty of St Germain was signed, his small legion of a few hundred marched from near Venice to Fiume in what they called the Impresa - the Enterprise. By the time he had reached Fiume, the ‘army’ numbered in the thousands, the vanguard crying “Fiume or Death” with D’Annunzio at its head in a red Fiat.

The only thing that stood in his way was the garrison of the Entente, soldiers who had been given orders to prevent D’Annunzio’s invasion by any means necessary. But amongst the garrison’s leaders were many sympathetic to D’Annunzio’s vision, some even artists themselves and before long most of the defenders had deserted to join the poet’s army. On the 12th September 1919, Gabriele D’Annunzio proclaimed that he had annexed Fiume to the Kingdom of Italy as the “Regency of Carnaro” - of which he was the Regent. The Italian government was thoroughly unimpressed and refused to recognise their newest purported land, demanding the plotters give up. Instead, D’Annunzio took matters into his own hands and set up a government and designed a flag (below).

The citizens of what had been a relatively unimportant port quickly found themselves in the midst of one of the 20th Century’s strangest experiments. D’Annunzio instituted a constitution that combined cutting-edge philosophical ideas of the time with a curious government structure that saw the country divided into nine corporations to represent key planks of industry like seafarers, lawyers, civil servants, and farmers. There was a 10th corporation that existed only symbolically and represented who D’Annunzio called the “Supermen” and was reserved largely for him and his fellow poets.

These corporations selected members for a state council, which was joined by “The Council of the Best” and made up of local councillors elected under universal suffrage. Together these institutions were instructed to carry out a radical agenda that sought an ideal society of industry and creativity. From all over the world, famous intellectuals and oddities migrated to Fiume. One of D’Annunzio’s closest advisers was the Italian pilot Guido Keller, who was named the new country’s first “Secretary of Action” – the first action he took was to institute nationwide yoga classes which he sometimes led in the nude and encouraged all to join. When not teaching yoga, Keller would often sleep in a tree in Fiume with his semi-tame pet eagle and at least one romantic partner.

If citizens weren’t interested in yoga, they could take up karate taught by the Japanese poet Harukichi Shimoi, who had translated Dante’s works into Japanese. Shimoi, who quickly became known to the government of Fiume as “Comrade Samurai” was a keen believer in Fiume’s vision and saw it as the closest the modern world had come to putting into practice the old Japanese art of Bushido.

The whole thing would have felt like a fever dream to an outsider. If a tourist was to visit the city, they would have found foreign spies from across the world checking into hotels and rubbing shoulders with members of the Irish republican movement while others did copious amounts of cocaine, another national pastime in Fiume. The most fashionable residents of Fiume carried little gold containers of the powder, and D’Annunzio himself was said to have a voracious habit for it. Sex was everywhere one turned and the city had seen a huge inward migration of prostitutes and pimps within days of D’Annunzio’s arrival. Almost every day was a festival, and it was an odd evening if the harbour of Fiume did not see dozens of fireworks burst above it, watched on by D’Annunzio’s uniformed paramilitaries.

D’Annunzio himself lived in a palace overlooking the city, Osbert Sitwell describes walking up a steep hill to a Renaissance-style square palazzo which inside was filled with plaster flowerpots the poet had installed and planted with palms and cacti. D’Annunzio would cloister himself in his rooms for 18 hours a day and without food. Immaculate guards hid amongst the shrubs to ensure he would not be disturbed. In D’Annunzio’s study, facing the sea, he sat with statutes of saints and with French windows onto the state balcony. When he wanted to interact with his people he would wait for a crowd to form over some issue, walk to the balcony and then ask what they wanted.

The Dream Turns into a Nightmare

Within a few months of Fiume’s annexation, the Italian government had failed to dislodge D’Annunzio and so instead came with a simple proposal. The city should have a referendum that would ask its residents whether Fiume should join Italy as a protectorate or continue to exist in its independent state. After his initial desire for it to be part of metropolitan Italy, D’Annunzio did not want to lose this enclave of radicalism to normal government. Eventually the matter was passed by the city’s councils and a plebiscite on a modus vivendi (mode of living) was scheduled for December 1919.

D’Annunzio, despite his anaemic appearance, was a powerful speaker and he took to the stage in Fiume to convince the population to vote against the proposal. It is likely that despite his charisma, the residents had probably become bored of the cocaine-fuelled yoga sessions and state-funded fireworks displays and voted overwhelmingly in favour of the Italian government by a margin of four to one. The votes had happened against a backdrop of sectarian violence between Italians and Serbs as well as other bullying methods from both sides to try and secure their ideal result.

D'Annunzio, furious, promptly nullified the result, refusing to acknowledge that Italy could do for Fiume what he had done. He took to his balcony and proclaimed to the citizenry that “We came here to win, we have sworn to win … Must we leave the axe embedded in the tree of destiny? No.” D’Annunzio was to go nowhere.

He set about trying to legitimise Fiume’s status in the world instead of handing over its keys to the Italians. Why join the League of Nations, D’Annunzio argued, when countries could instead join the newly created League of Fiume. The League had been set up as an alternative to the more well known League and was aimed at non-aligned nations. It was headed by Fiume’s Foreign Minister, who Sitwell calls “the only bore in [the country].”

One of the first prospective members of the League was the newborn revolutionary Irish Republic, and while their parliament pondered joining it was ultimately worried that doing so would anger the United States. Curiously, the League and Fiume were the first to officially recognise the Soviet Union with the hope that the USSR would join its “oppressed brother” on the Adriatic. While Lenin demurred on joining, he did send D’Annunzio a pot of caviar and a charming letter that described D’Annunzio as the “only revolutionary in Europe.”

There is an old British Pathe silent newsreel from 1920 that survives today and one can watch online; it shows D’Annunzio reviewing his soldiers in Fiume. D’Annunzio, dwarfed by his lieutenants and the surrounding buildings, struts down a street saluting almost continuously as he passes some of his legionaries ready with their military bicycles. At the end of it he makes a speech from a balcony, waving his hand before making straight armed salutes, copied by his entourage.

We cannot hear what he is saying, but it likely included the national cry of Fiume: “Eia, eia, eia! Alala!” The first three words are the Sardinian equivalent of “hip hip” in “hip hip hurray” and “Alala” which D’Annunzio had taken directly from the Iliad, in which Achilles uses it as a war cry. Benito Mussolini, a friend of D’Annunzio and long-term correspondent, visited Fiume, and there gave inflammatory speeches. It is not hard to understand, watching the newsreel and its black-clad paramilitaries with lightning flashes on their sleeves, where Mussolini may have got much of the inspiration for his Blackshirts. D’Annunzio was even referred to as “Duce” (Leader) in Fiume, a title that just two years later was adopted by Mussolini.

Man Cannot Live by Cocaine Alone

Fiume, which had once seen good trade as an Austrian port, saw a sharp decline in traffic with an international embargo led by the Italians. As a result shipbuilding and manufacturing, two of D’Annunzio’s pillar Corporations, became shadows of their former selves. With a lack of raw materials and an economic policy based on poetry and put into action by some of Europe’s strangest radicals, there was not much productivity.

The city acquired its own currency, the Fiume Krone, which were Austro-Hungarian banknotes with “CITA DI FIUME” stamped over them. In theory a Fiume Krone was worth 40 Italian cents, but with no gold reserves or strong economy to back it up, a Krone sold on the black market for around 20 cents. The currency rapidly inflated and was devalued, leaving little trust in the government of Fiume by its people. The black market grew and grew, providing supplies held back by the Italian blockade and organised crime began to take hold. With the whole world turned against Fiume, D’Annunzio could not access international credit or sign free trade agreements. To combat this, D'Annunzio instructed Guido Keller to obtain crucial supplies for Fiume through piracy and theft. Keller used his aviation skills to conduct daring raids on farms in Italy and Austria to steal livestock, on one occasion a pig broke through the bottom of his plane and he landed with its trotters sticking out.

Law and order in Fiume was managed by D’Annunzio’s enforcers, the Arditi – The Daring Ones. Most of the Arditi had been members of the Italian Army in the war but many were younger ideologues captivated by the poet’s vision. The Arditi wore smart black uniforms and their elites would be reviewed by D’Annunzio daily while their bands marched through Fiume’s streets playing neverending patriotic music all day long. During the plebiscite, it was the Arditi that roamed the city beating up any of D’Annunzio’s opponents and it was the Arditi that ran the polling stations, but even with these enforcers the people voted for the end of the Fiume regime.

As the economic situation declined, the Arditi brought more and more troublemakers before Fiume’s slightly esoteric criminal justice system created in the city’s charter that was called “The Court of the Cursed”.

By mid 1920, the Italians had begun to lose patience. The election that year had seen the installation of Giovanni Giolitti as the Prime Minister, a liberal who despised D’Annunzio’s vision and proto-fascist ideals. In 1915, D’Annunzio had called Giolitti a traitor, which didn’t help Fiume’s hopes.

Over the summer Italy began to negotiate with Yugoslavia to determine a final settlement on the matter of Fiume, to fill the loophole still left by the demise of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In November 1920 the two countries signed the Treaty of Rapallo, which was remarkably unpopular amongst both Italians and the people of Yugoslavia. However, it did categorically address the issue of Fiume. Gone would be the Regency of Carnaro founded by D’Annunzio and in its place “The Free State of Fiume” which would be governed not by a poet and his karate sidekick but by a bureaucratic government acceptable to both countries.

Predictably, D’Annunzio was furious. To protest the Treaty, Keller once again took to the air on a daring mission authorised by his Duce. He flew his aircraft from Fiume to Rome, where he dropped flowers on the Vatican before bombarding the Italian parliament with a chamber pot filled with turnips and carrots. A note was attached to the vegetables addressed to members of the Chamber of Deputies: “To the parliament and government based on lies and fear, the allegorical embodiment of their value”.

Meanwhile, sectarian violence had completely taken over the streets of Fiume. Croatians had bombs thrown at them by Italians and Serbs were locked up without trial and their homes handed over to supporters of D’Annunzio. In response, Italian soldiers would be picked off by Serbian guerillas and it quickly descended into a cycle of pointless retribution. Crime soared, and fearful citizens slept with their livestock in their bedrooms to prevent theft. In terms of economy, the only lively industry became the production of ammunition and hand grenades.

By this time, D’Annunzio had become even more reclusive and spent much of his time with his pet parrot given to him by Keller. His cocaine habit grew and grew, it having begun during his wartime flying and he would communicate with his officials by letters while his idealistic young legionaries continued to practise yoga in the city centre.

The End

To protest the Treaty of Rapallo, D’Annunzio sent soldiers to occupy two small islands off the coast of Fiume that had under the treaty been assigned to Yugoslavia. This was the final straw for Giolitti and the Italian government. In short order, the Italian military retook the islands for Yugoslavia and tightened the naval blockade on Fiume to prevent any more such antics.

In the week of Christmas 1920, The Italian Government dispatched 8,000 soldiers led by one of Italy’s most famous generals, Enrico Caviglia. Caviglia presented D’Annunzio a simple ultimatum, hand over Fiume, recognise the Treaty of Rapallo and walk away. D’Annunzio refused and on Christmas Eve, Caviglia launched an attack by land. For hours the two sides were engaged in fierce fighting, with D’Annunzio’s legionaries, many of whom had served during the First World War, using machine guns and explosives to fight back. For Christmas Day, the two sides agreed a truce and the fight began again on the 26th with significant bloodshed. Caviglia had enough and used something the Regency of Carnaro could not afford: battleships. For three days, two Italian dreadnoughts bombarded Fiume furiously and still D’Annunzio held out even after a shell was put through his own office window.

Caviglia sent a message once more, surrender or the shelling will obliterate what is left of Fiume. The town’s notables came to D’Annunzio and begged him to accept it and finally he agreed, although some suggest he may have even tossed a coin to make the decision for him. He had eventually been defeated by the very country he created Fiume for, by the government he hoped to embolden to take what he believed was Italy’s by right. But there was to be no punishment for D’Annunzio, his troops laid down their arms and he simply went back to Italy a few weeks later. While he would never be as powerful or as relevant as when he was driven to Fiume in his red Fiat, he never disappeared.

As Benito Mussolini rose to power, a new Duce, D’Annunzio remained in touch. Against the backdrop of being a threat to Mussolini’s success, D’Annunzio had a mysterious accident where in 1922 he fell out of a window just before he had arranged to have a meeting with Mussolini on the future of Italy. Theories still abound that Mussolini had arranged the defenestration to cripple him. For the remaining 16 years of his life, D’Annunzio lived in relative peace and was even made a Prince in 1924 by the King of Italy. He received regular bribes from Mussolini to supposedly prevent him re-entering politics. He would not live to see the Second World War, or the fall of Italy and Mussolini as in 1938, D’Annunzio died after a stroke, on the shores of Lake Garda where he had retired to.

The Regency of Carnaro, though short-lived, remains a fascinating and significant chapter in European history, like a half-remembered dream. This fantasy of a poet, with its dizzying spectacle of fireworks, corporatist futurism, and cocaine-fueled excess, may have been crushed, but its impact resonated far beyond the sapphire-blue coast of the Adriatic. The black-clad Arditi who marched through Fiume's streets would become the model for Mussolini's Blackshirts, and the title of "Duce" that D'Annunzio bore would be inherited by the future dictator of Italy from a man he believed to be as significant a prophet as John the Baptist. Irredentism would shape Italy’s next few decades. The Regency of Carnaro was a strange and captivating prelude to the rise of fascism and the flames of another world war.

Today, Fiume is Rijeka, a city inherited by Croatia from Yugoslavia - a transfer made in the aftermath of Italy’s defeat in the Second World War. Around 100,000 people live there and in 2020 Rijeka was even the European Capital of Culture. While there is little evidence now that this port town had once been the world capital of radicalism, D’Annunzio would have been pleased that in 2018 it was declared that Italian would be one of Rijeka’s official languages and bilingual signs now fill the streets – although none direct residents to publicly funded yoga.

What a great read. Hughes-Hallett presents D’Annunzio as a bizarre mixture of Wilde, Kipling and Cecil Rhodes, but mysteriously irresistible to both women and men, and still celebrated in streets, squares and public buildings over Italy.

There’s a book that needs to be written on cocaine a century ago (maybe it has been). I recently read Anthony Beevor on Russia’s post-revolution Civil War. The Whites were pretty useless at securing supplies of weapons and food, but they never ran out of cocaine, apparently.

This sounds more like a fanciful work of fiction than actual history. But truth can be stranger than fiction.