The Story of the Coconut War

Sometimes there are rules we don’t like. For example, if you live in a country, you have to follow its laws and pay its taxes, and if you don’t, the only option is to either be punished or move to another country. But imagine for a moment if you could live in Britain but follow the laws of France or vice versa. It would be a pretty strange state of affairs, but it’s precisely how a volcanic archipelago in the South Pacific was governed for almost a century.

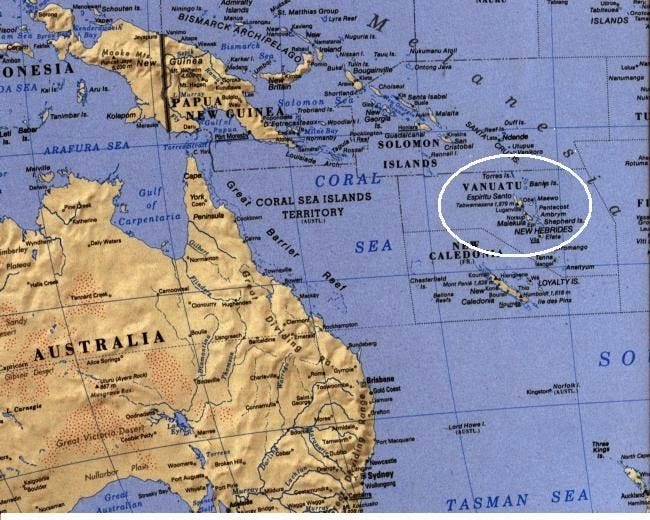

The chances are you could not pick out Vanuatu on a map, but for the sake of placing this story, it is an island republic between Australia and New Zealand, more or less on the same line of latitude as Papua New Guinea. It has around 300,000 residents, most of whom are indigenous Melanesian people and have likely been there for a few thousand years. Europeans first discovered what is now Vanuatu in 1606 when it was ‘claimed’ for the King of Spain by a passing sailor who named it Espíritu Santo. No European returned for almost two centuries, but in the late 18th Century, a succession of French and British explorers from Captain Cook to Captain Bligh passed through, the former renaming the islands the New Hebrides, a name which stuck.

It was soon discovered that the New Hebrides had a plentiful supply of sandalwood, coconuts, and land perfect for cotton plantations. As a result, over time there was a massive influx of settlers on the island, primarily British and French planters hoping to make money from farming cotton by using cheap Melanesian labour. By the turn of the 20th Century, while there were hundreds of these planters were on the islands, there wasn’t a single bit of formal governance and, as a result, pure anarchy.

With growing concern at the exploitation of indigenous labour and lack of authority, the British and French governments eventually agreed to formalise the administration of the New Hebrides, but neither wished to give up their perceived rights to be responsible for it. As a result, a condominium was formed, where both Britain and France had equal roles in government with separate legal systems, separate police forces and even separate financial set-ups.

Someone in the Anglo-French Condominium of the New Hebrides could decide they wanted to be governed by British immigration rules but be tried in the French criminal courts while setting up their business according to the British registration system. All documents had to be signed by the Resident Commissioner appointed by each country, who operated out of their separate compounds marked out by their respective flags that flew at the exact same height – until a junior British official on their first day was tricked into letting the French one fly higher.

Every colonial bureaucrat on the island had a mirror equivalent opposite number, while postage stamps had the emblems of both countries and were payable in two currencies. Moreover, Islanders had the citizenship of neither Britain nor France and were not issued passports but ‘travel documents,’ signed by both nations’ commissioners and largely invalid for travel.

Bemused Australians in the New Hebrides renamed the Condominium “the Pandemonium” – which was understandable when one country has two police forces with different uniforms, two health systems and two entirely distinct systems of law. To add confusion, the two police forces would regularly swap duties to not give any impression of seniority.

If there were any disputes, there was a Joint Court with judges from each country and a President appointed by the King of Spain - because why not. This became an issue when Franco abolished the Spanish monarchy, and for the rest of the islands’ existence, the Joint Court had no president. When passing judgement, the Joint Court would decide if the conviction should be British or French, depending on the circumstances.

Even the anti-colonial movements and political parties existed in pairs; groups were dedicated to fighting French rule and others to British government, with entirely different philosophies and objectives. This reached a head in the 1970s when independence discussions began regarding the New Hebrides.

The British Government was unopposed to the idea, providing stages to self-government through local elections and eventual independence, supporting political parties. However, the French Government, prompted mainly by European business owners, disagreed with this premise and wanted the New Hebrides to become a permanent overseas colony as New Caledonia and other French Pacific islands remain to this day. While Francophone parties attempted to boycott elections and the independence referendum, moderates were able to win by a significant margin, and independence was scheduled for the summer of 1980. Father Walter Lini, an Anglican priest and head of the moderates, led the new republic, which was to be called Vanuatu.

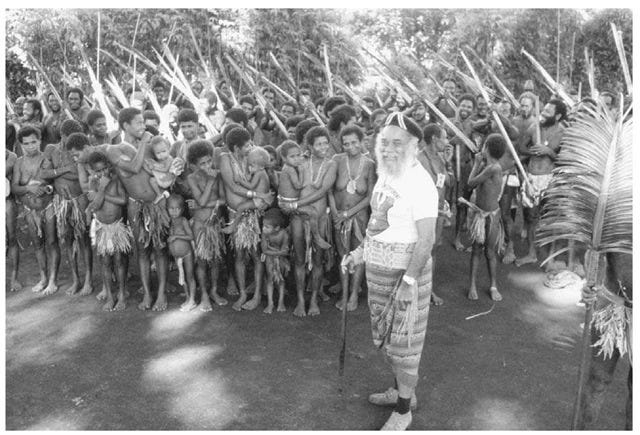

This all occurred against the backdrop of a significant economic boom on the New Hebrides, prompted by its strange legal status allowing all sorts of tax loopholes and encouraging the establishment of banks and financial companies aiming to provide tax haven services to Europeans. With that came tourism and a growing awareness of the unique situation on the island, including from the American libertarian organisation – the Phoenix Foundation. For some time, the foundation had been dedicated to creating a libertarian nation-state backed by millions of dollars from donors. Having failed elsewhere, the group set its sight on the New Hebrides/Vanuatu and its upcoming independence. It provided one of the leading anti-government activists, Jimmy Stevens, with a large amount of cash, weapons and military radios to launch a rebellion in return for promised concessions such as casino rights. Stevens claimed to be a second Moses and had 23 wives and many more children. Thus in June 1980, the so-called Coconut War began when Stevens declared he had achieved the independence of his own country, the Republic of Vemerana.

In the bizarre conflict, Father Lini appealed to Britain and France to send troops to put down Stevens’s libertarian rebellion; however, once the French paratroopers arrived, they refused to act against the rebels under secret orders from President Francois Mitterand.

It eventually fell to the British Army and Royal Marines, whose officers believed while en route that the New Hebrides was in Scotland not the Pacific, along with troops from Papua New Guinea to put down the rebellion. By the end of August, the farcical revolt had ended quickly because the rebels were largely only armed with bows and arrows.

It was only at Jimmy Stevens’s trial that the truth emerged that the Phoenix Foundation and French landowners had promised him $250,000 for launching his rebellion. Instead, he was sentenced to 14 years in prison and was released in 1991.

Today in Vanuatu, there is only one police force and one currency. It is a diverse paradise, with almost every religion on earth represented, including some who even worship Prince Philip. These days, you do not need to go and get permission from an Englishman and a Frenchman to leave the country, and nowhere does a judge appointed by the King of Spain get to interfere with your life.

References:

Woodward, K. (2014). A Political Memoir of the Anglo-French Condominium of the New Hebrides. ANU Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt13wwvr8

Shears, R. (1980). The Coconut War: The Crisis on Espiritu Santo. Cassell Australia.

Guthrie, General Sir C. (2000). Desert Island Discs. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00949n6

“Diplomat who fought 'Coconut War' for Vanuatu independence.” (2014). Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/national/diplomat-who-fought-coconut-war-for-vanuatu-independence-20140216-32u3a.html

"British Answering New Hebrides Call; Company of Marines Being Sent 'to Provide Stability'". (1980). New York Times.

Ned, I love this, thank you and it's good to find your site here.

I wrote an article in part about my trip to Vanuatu here:

https://3quarksdaily.com/3quarksdaily/2022/12/on-the-road-vanuatu.html

and found precious little background stuff to cite. Thanks for this.