In the Hall of the Dragon King

The flight attendant leant across me and without warning snapped up the plastic window blind. Before I could say anything, he points his finger to the window and says, “Mount Everest.”

I look out and I see a particularly beautiful carpet of white clouds, but at what I first thought was just a continuation of their patterns I realise I am in fact looking at the roof of the world.

“Count one, two, three and that is Mount Everest,” he says before returning to the galley. I do as he say, counting the peaks and there it is, the highest peak in the world.

For as long as I can I stare at the mountains, watching them fade as our aeroplane begins our turn towards Delhi. As they disappear to be replaced by the ever present Indian haze, I look back on short time I have spent in the Kingdom of Bhutan in the foothills of those mountains. I come to realise that while I have learnt a lot I didn’t actually understand it any better than a week earlier when I stepped off the flight to Paro, our DrukAir Airbus having negotiated the narrow passes and turns that lead to an airport that has only 24 pilots qualified to land or take off there. The final turns are made by the pilots spotting a particular house’s red roof, a house passengers can easily see into as the plane swings to approach the runway.

Bhutan has long been a place I had wanted to visit, but it isn’t as simple as booking a ticket.

It would be remiss not to quickly situate Bhutan and its history for those unaware. It is a small kingdom east of Nepal and nestled between India and China. It has a population of around 750,000, almost all of whom are devout Buddhists. It was once a land of feuding Tibetan chieftans who were united in the 1630s by a remarkable warrior and Buddhist lama called Ngawang Namgyal. Namgyal died in 1651, but his death was kept a secret from the country for more than 50 years, with officials simply saying that the king was “on an extended retreat” and continued to keep Bhutan together by issuing decrees in his name.

While Namgyal was seen as the spiritual leader, he also established a temporal monarchy which in a slightly modified form still exists today under the leadership of the Wangchuk dynasty. The King of Bhutan’s title is the Druk Gyalpo, which literally translates to Dragon King. Over time Bhutan, being small but strategically located, faded in and out of the spheres of influence of the day from the Mughals to the British Raj. It would have been subsumed into the latter like other princely states, but in the 19th Century a British civil servant placed some files relating to Bhutan into a folder marked “External” instead of “Internal,” a small decision that ensured it remains an independent country today, albeit one “guided” on matters of defence and foreign affairs by a treaty with India.

The country only opened its borders to foreigners in 1974, to mark the coronation of the Fourth King, Jigme Singye Wangchuck. His Majesty saw the opportunity to take advantage of his accession to showcase Bhutan and its unique culture and traditions to the world, but was also aware that unrestricted tourism would put those at risk. Over time, this developed into a vision known as “High Quality, Low Volume” tourism. All visitors must have a guide and driver and also pay a daily fee - currently $100. In 1974, 287 foreigners visited Bhutan, and in 2019 more than 70,000 fee paying tourists came.

As a result of this policy, the trips are largely cultural. You take hikes in unimaginable scenery, watch local festivals where masked creatures tell villagers morality tales, and sit with locals to eat dishes made up mostly of chilis. For fun people relax with the national sport of archery, singing deliciously rude songs to put off their friends while they take shots. Tourists get to have a go but the target is brought closer and you get to use the same kind of bow young children do. Civil servants go to work in traditional dress and robe-clad monks pepper society. In the five days I spent there, much was spent talking to our compulsory guide who was a lovely man named Yarab, who had once been on the Bhutan national football team. One story Yarab told me was that of Bhutan’s transition to democracy.

The previously mentioned Fourth King oversaw Bhutan’s transition into the modern world - but with a catch. Bhutan’s development could not come at the cost of its people’s happiness. Thousands of kilometres of roads were built, free at point of use clinics quickly filled the country, and electricity and telephone hookups turned King Jigme Singye’s isolated kingdom where almost no one had access to healthcare or education into a remarkably healthy and literate little state in the space of just a few decades. Much of the money to make this possible came from selling hydroelectricity generated by dams that are powered by Himalayan glaciers. The Fourth King explained that: “water is to us what oil is to the Arabs.”

Despite the rapid economic growth, Bhutan’s culture and traditions were protected. By 2006, the Fourth King believed his job to be done and he announced his abdication, passing power to his son Jigme Khesar Namgyel who became the Fifth and present King of Bhutan. One of his father’s last acts was to finalise a draft constitution for Bhutan, one that would take away the monarchy’s absolute power and turn the country into a constitutional monarchy with parliamentary democracy.

But first the Bhutanese people, largely rural and disconnected from the outside world, had to be taught what democracy was. Yarab told me at first it was seen with immense distrust, and it fell to the father and son kingly duo to make a tour of the country to convince them otherwise. In 2007 this culminated with the population getting to try it out in two nationwide mock elections where voters could pick from abstract ideas rather than candidates.

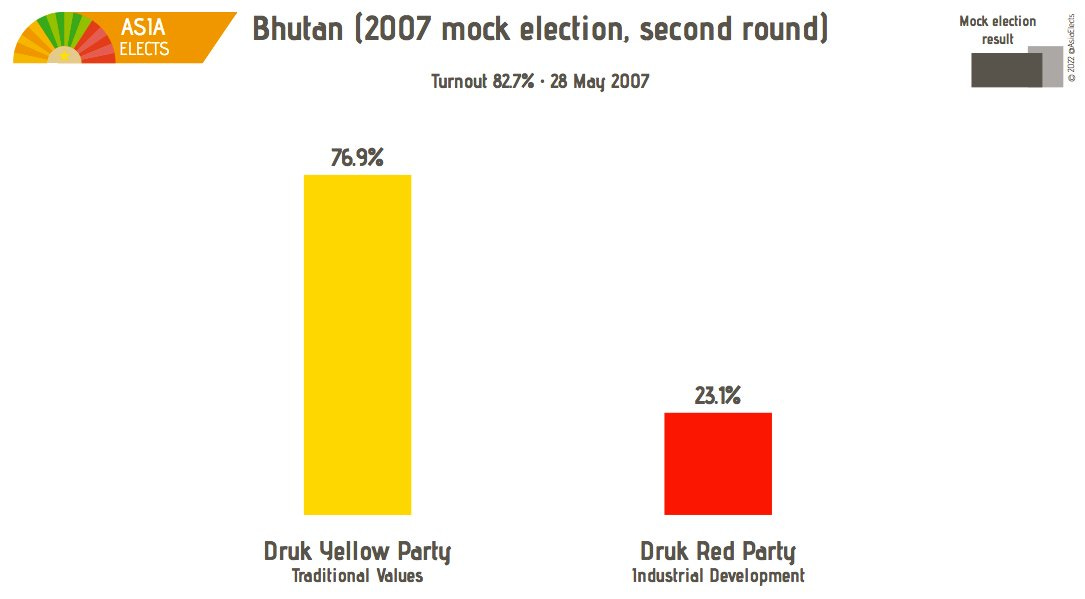

Ballot papers had four imaginary parties on them, each named after a colour (Blue, Green, Red, and Yellow) and with local high school students chosen as constituency candidates. Later there was then a mock runoff and the Yellow party swept to victory in 46 of the 47 constituencies on a 67 per cent turnout. It is no coincidence that the colour yellow in Bhutan is the colour symbolic of the monarchy and the king.

By mid 2008, the first real elections had been held and an Upper and Lower House elected for Bhutan and in July the draft constitution was enacted by the kingdom’s first democratic government.

I thought the story was remarkable, but it got even more interesting when a senior Bhutanese official casually told me that Ngawang Namgyal had also been informed about the elections. Namgyal was that first ruler of Bhutan I mentioned earlier who was meant to have died in 1650 and whose passing was hidden for 50 years. I asked them to explain in case I had misunderstood. It turned out that it is believed that Namgyal is still very much alive, having self-mortified himself in the ancient Buddhist tradition and now he resides in a monastery. Very few are permitted to see the great Lama, but each day he is brought food and water and the King and highest monks will often go to him to consult on important issues. “He’s simply resting,” my new Bhutanese friend told me, smiling.

While I only spent time in the north of the country, I learnt that the King had recently launched a project in the plains of the south of Bhutan near a place called Gelephu where he plans to build a city the size of Singapore that will be a “mindfulness city.”

The city, designed by a Danish firm, will feature an airport that doesn’t require the hairpin mountainous turns that the country’s only current international airport in Paro and would be capable of taking wide-body aircraft. By it being in the south, it will allow the rest of Bhutan to be insulated from both foreign interference and cultural damage. But even in Gelephu, buildings will strictly limited in size and design and nature will be left to thrive amongst the buildings while its hospitals will be able to bring the best of eastern and western medicine to bear. Situated between India and China, Gelephu will be a key economic hub but it is also important to the King that any development doesn’t betray the unique character and history of Bhutan that makes it so special, but this would be impossible as once again Ngawang Namgyal is being kept up to date on plans and consulted on Gelephu.

Back on the plane, Mount Everest disappeared and I shut the window blind again, sad to have left the sense of peace and calm that Bhutan allows to percolate through your entire self. But as I said, I still did not understand it. These days we are all obsessed with travel, and have largely unfettered access to the world to exercise it. Many of us go to places our grandparents could barely imagine, and yet we all have the same experiences. We take remarkable pictures of wonders across the world and share them on social media but manage to avoid capturing the other thousand people queuing up behind us to take the same photo. Much travel today is replicated and homogenised, I can for instance say that I have had the same Caesar salad in Four Seasons hotels on four different continents.

In Bhutan there was not a Caesar salad in sight and it was made clear that I was a welcome guest passing through but it was not expected I come away with even a basic level of understanding because why should I? There are few places I can think of that will give you such a wonderfully enlightening sucker punch and months later it still feels refreshing.

Another "mountaintop kingdom" (well, at least historically) like this is Ethiopia. Ostensibly much easier to access than Bhutan with arguably a much less enlightened government, Ethiopia's still stands as a unique and ancient culture that was largely insulated from outside influence until the late 20th Century. As a result, tradition and modernity interact in very fascinating ways there:

They still use a 13-month calendar, still have a distinct way of telling the time (the day starts at 6am), still have Africa's only indigenous alphabet (with an intimidating 230 characters!), and still largely follow Orthodox Christian and Muslim practices that predate and are very distinct from the newer varieties that you'll see in countries that you'd more readily associate with those world religions (Ethiopia is mentioned in both the Bible and the Qur'an and has a decent claim to being both the first officially Christian and Muslim countries, respectively).

Things are certainly more globalized than when I was living there in the early 2010s, back when you couldn't even get a 2G data connection from the state telco monopoly and voice service was spotty-to-non-existant. But Ethiopia still strikes you as a sui generis type of place that's just hard enough to navigate as a tourist that you get that special experience of being a traveler to a place that doesn't exist on your behalf. I woke up every day there and found the most basic assumptions of my normality questioned. I felt constantly mystified and intrigued. I also found it extremely frustrating regularly. But that's the cost of truly encountering difference!

This was delightful to read! I did not know about this new city in the south of Bhutan. I'm from Bangladesh (which lies across the Indian border from Bhutan). The King of Bhutan will be visiting us in the next few days. Bhutan is planning to develop a special economic zone in northern Bangladesh near the Indo-Bhutan border. I hear this SEZ will be a green zone, eco-friendly, sustainable and all. So your post kind of completes my jigsaw puzzle. A potential Bhutanese SEZ in Bangladesh will probably complement the sustainable city being planned on the Indo-Bhutan border.

Bhutan has a very cool Dragon King!