England's Lost Monastic World

The cheap cup and saucer rattled slightly in the elderly monk’s hands as he opened the coffee urn’s tap. I had asked him a question and he was about to respond when he spotted a shortbread biscuit, with one secured safely on his saucer he finally began to answer.

He had joined this monastery as an 18 year-old when King George VI was still on the throne. He is now 89 and has no plans to be anywhere else. In the intervening 71 years, he has edited multiple translations of the Bible, written more than 20 books, and taught thousands of pupils. With little of value to add, I largely listened. He eventually told me he had to go as he had some mowing to do and, hitching his black cassock, wandered off.

I had come to Ampleforth Abbey for two reasons. The first was to have an adventure with some friends I was visiting nearby and the second was because my father had been to school there for five years of his life in the late 1960s. Ampleforth is a Benedictine monastery in North Yorkshire that sits in its own valley overlooking fields of sheep dotted like they are in a John Constable painting and stands as a living testament to a tradition that once blanketed England. Created after the 19th Century Catholic Emancipation, the monks for many years ran a school of several hundred boys, a school which is still on site but now both legally separate from the monastery and co-educational.

Yet, as I watched the elderly monk amble away to his gardening, I couldn't help but reflect on the vast tapestry of knowledge, culture, and spirituality across England that was torn apart by King Henry VIII's dissolution of the monasteries in the 1530s. For those unaware, this was part of the English Reformation and the king’s desire to raise money to fund his many wars and even greater debts by selling the monasteries’ lands and valuables.

The monk's casual mention of mowing seemed almost comically mundane, yet it echoed a truth that has persisted through centuries: monasteries were not just houses of prayer, but vibrant communities that shaped the very landscape around them. As I stood there, I tried to imagine the country as it once was, a land where every few miles you might encounter a monastery, each a beacon of learning, spirituality, and economic activity.

Each of the marks on the map above represents a monastery in England and Wales that existed prior to their dissolution. Each point represents not just a building, but a centre of knowledge, economy, and spirituality that anchored local communities for centuries. Hundreds of such places disappeared almost overnight.

Desperate to grasp the magnitude of this loss, I forced my friends into their hatchback, and we set off for Fountains Abbey, just a few miles from Ampleforth's doors and for centuries a large Catholic monastery. As we approached, the ruins loomed before us, a skeletal reminder of former glory now accessed through a cheerful visitor centre that sold merchandise and fresh sponge cake.

Standing amidst the crumbling walls, I nearly stumbled over a plaque that read: "CAUTION - ECHOES OF THE PAST CAN BE HEARD HERE." The irony wasn't lost on me. These stones, once witness to centuries of chanted prayers and scholarly discourse, now stood silent. Yet, in that silence, the weight of loss seemed to press in from all sides.

The abbey wasn't merely built; it was strategically placed within this valley, part of a sacred geography that once blanketed England. Monasteries like Fountains were often situated in remote locations, their very isolation serving both practical and spiritual purposes. They became transformative forces, taming wilderness both literally and symbolically, turning undeveloped land into centers of learning, spirituality, and economic activity. The monks who chose this spot didn't just build an abbey; they cultivated a unique spirit of place that continues to touch visitors today, even as nature reclaims the ruins.

Yet, as I turned from the crumbling walls to check my smartphone and look at the photos I had taken, I was reminded of the stark contrast between this rooted, place-bound existence and our modern, increasingly placeless world. Where monks once spent lifetimes in one valley, many of us now flit between cities, countries, and virtual spaces, our sense of place becoming completely fluid. Even for this email, I have edited it as a draft in at least four different countries. Standing in Fountains Abbey, or walking the grounds of Ampleforth, offered a poignant counterpoint to this sense of placelessness. These sites remind us of the power of a life deeply connected to a single place, of the richness that can accumulate when generations pour their devotion and labor into one spot. In a world where we can virtually visit any place on Earth, these ruins and living monasteries call us with their energy back to the profound importance of being present, truly present, in a place dense with history and meanings.

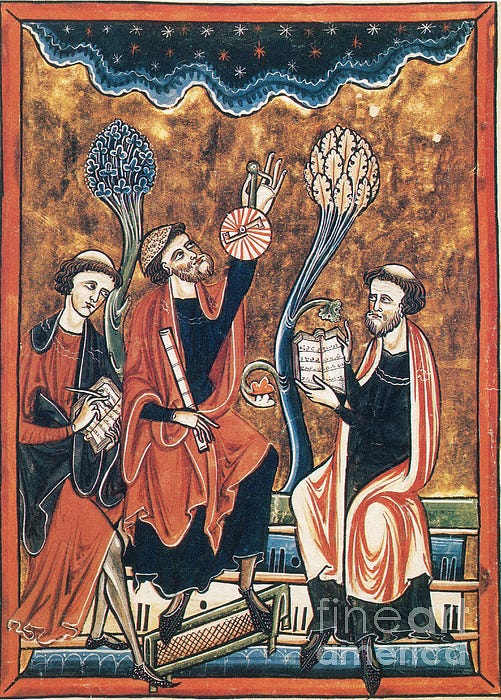

I closed my eyes, trying to imagine the refectory bustling with activity - the scrape of pewter plates, the murmur of conversation in both deep Yorkshire dialects and in Latin, the rustle of robes. Here, in this very spot, monks once pored over manuscripts, preserving and advancing knowledge that spanned from theology to herbal medicine, from agricultural techniques to architectural innovations.

The dissolution didn't just silence prayers; it silenced a vast library of practical and spiritual wisdom. Monastic gardens, once laboratories of early pharmacology, were left to grow wild. Agricultural techniques, honed over centuries, were lost as lands changed hands. The very stones of the abbey, once a testament to architectural expertise, began their slow crumble into romantic ruins.

But the loss extended beyond the tangible. As I wandered through the nave, its soaring arches open to the sky, I thought about the concept of sacred space. For medieval people, these monasteries were more than buildings - they were thin places where heaven and earth seemed to touch. We see our urban skyscrapers now as normal buildings we walk past, but imagine to the eye of a rural English peasant that an abbey like Fountains would almost certainly be the grandest structure they had ever seen. The dissolution didn't just change who owned land and fields, it fundamentally altered how people interacted with the divine and saw God.

The economic impact of the loss of such a place must have been seismic. Fountains Abbey, like many others, was once the heart of a complex economic ecosystem. It provided employment for hundreds, drove trade, and offered a safety net for the poor and sick. As the abbey fell silent, so too must have the bustle of commerce and industry that once animated the surrounding countryside.

Returning to Ampleforth, the contrast was stark. Here, the tradition lives on, adapted for the modern world but still recognizably part of that ancient lineage. I thought of my father, who had walked these same grounds as a schoolboy in the late 1960s, and I thought of Father Adrian Convery.

When my father had been terminally ill, I had an email correspondence with Father Adrian, a monk at Ampleforth. Father Adrian had written to me and said that he had been my father’s housemaster many decades prior. He promised he would pray for my father, and when he died he made that promise again. When I was invited up to North Yorkshire, I had hoped to meet Father Adrian but I learnt he had died earlier this year. The sense of connection across time and space was palpable. Before leaving, I made sure to say a prayer for Father Adrian, completing a circle of spiritual care that spanned generations and tied me, however tenuously, to this place and its enduring tradition.

As I walked to our car, I caught sight of another monk, reading a book in his hand and striding along a path and somehow not stumbling once. For a moment, superimposed on this scene, I saw an echo of countless monks who had walked similar paths over the centuries - at Fountains, at Glastonbury, at hundreds of other sites now reduced to picturesque ruins.

The dissolution of the monasteries was more than a political act or a religious schism. It was the unraveling of a way of life, a network of knowledge, and a destruction of a concept of sacred space that had defined England for centuries. Yet, standing in Ampleforth's peaceful valley, watching the elderly monk on his slow perambulation, I was struck by the resilience of tradition. Though diminished, it endures - in places like Ampleforth, in the ruins that still dot our landscape, and in the subtle ways it continues to shape our understanding of community, learning, and the sacred.

As I left the grounds, the words on that plaque at Fountains echoed in my mind. Indeed, if we listen carefully, those echoes can be heard not just in the ruins, but in the living traditions that have survived against all odds. They remind us of what was lost, but also of what endures - a testament to the indomitable nature of faith, place, and human connection.

What I’ve been reading:

The Narrow Corner: I actually read this last year but never recommended it at the time. It is one of Maugham’s lesser known stories but is a very well written account of a South Sea voyage and perfect if you are travelling to Indonesia or the Spice Islands any time soon.

The Surfer's Journal: While not anything approaching a serious surfer, the Surfer’s Journal has become one of my favourite magazines. It is beautiful and tells stories from how the tuna has inspired the shape of surfboard fins to interviews with musicians and artists. I highly recommend a subscription.

Like virtually everything else of value and consequence, whether physical or spiritual, destroyed over the course of history, we can thank our pathetic collective subservience to the political parasites of the day. Until and unless we find our collective spine, they will continue their rampage.

The protestant reformation in England was a truly devastating time, but in some perverse ways we were lucky. On the continent, a lot of important monastic institutions were thoroughly smashed by the Napoleonic wars. Ironically, the collegiate echo of monasteries (i.e. Oxbridge colleges) have survived in England where the collegiate universities of Europe have been de-collegiated by foreign powers (also Napoleon: Salamanca and Coimbra) or by internal strife (the University of Paris, multiple times). On a similar theme, a substantial slice of monastic knowledge/ book art was saved by Archbish Matthew Parker and deposited in Corpus Christi College Cambridge.